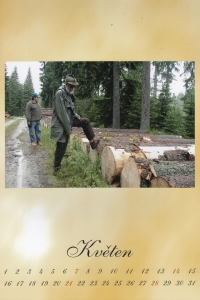

Fighting pests in dying forests resembled a military crusade

Download image

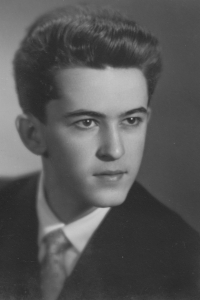

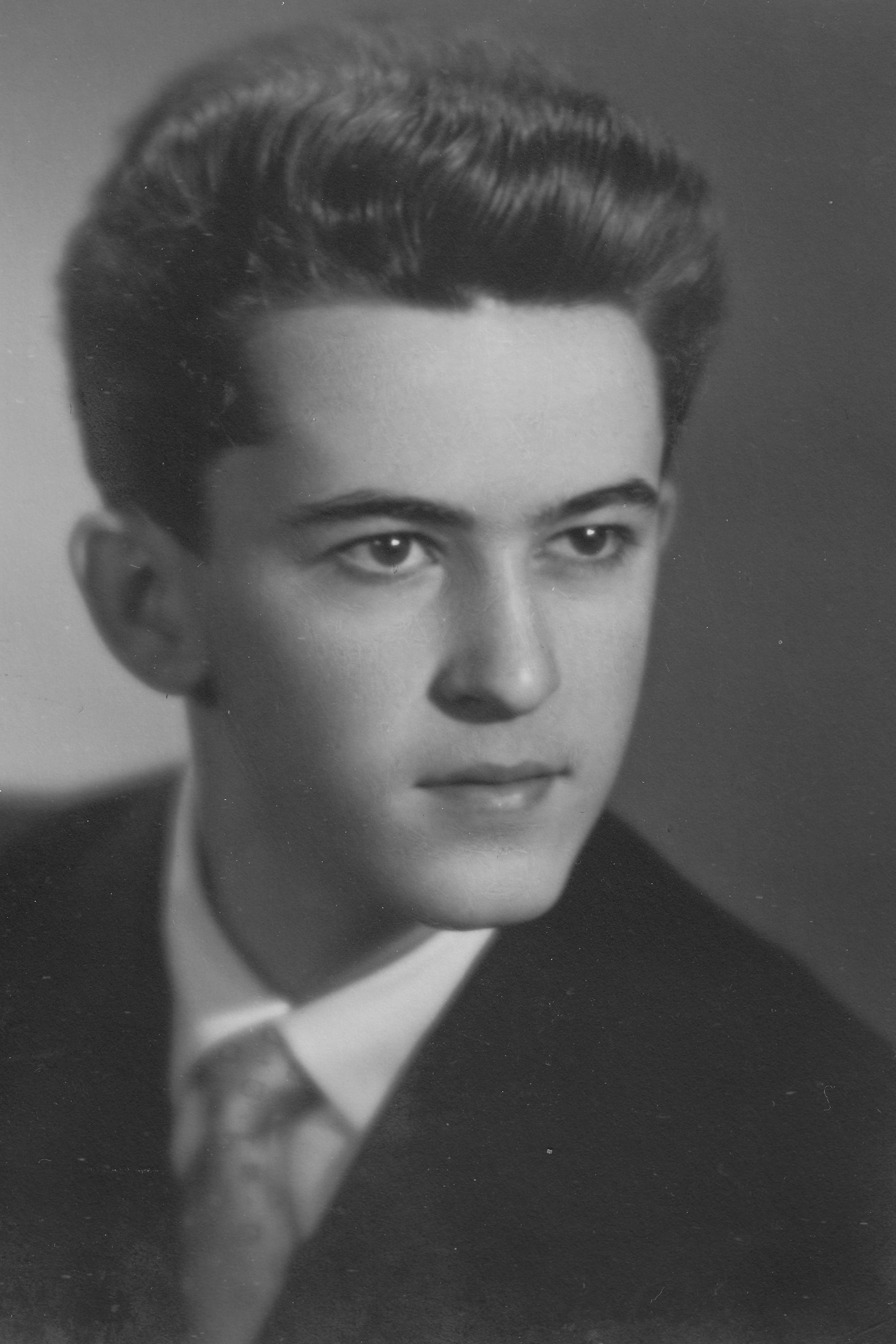

Petr Kadleček was born on 30 January 1944 in the St. Apollinaris Hospital in Prague. He had a brother, Jiří, five years older. His father, Antonín, worked as a grinder-machinist in the Jawa factory, the so-called Janečkárna. Mum Marie worked as a clerk mainly in banks. Father took part in the fighting of the Prague Uprising in May 1945. In 1953, he paid the price for the communist currency reform and lost a lot of money, which he saved for his own locksmith shop. He publicly criticized the currency reform in the factory and was arrested by the police at home. Although he was released the next day, he lost his job at the Janečkárna factory and was not hired anywhere else in his profession. He earned a living as a construction labourer, later reestablishing himself in his trade and going to foreign fairs. After primary school, Petr Kadleček graduated from an eleven-year school, similar to today’s grammar school. After graduating from high school, he entered the University of Agriculture in Brno in 1961, where after five years, he passed the state examinations at the Faculty of Forestry. As an undergraduate, he was in the army for one year. In 1967, he joined the East Bohemian State Forests as a forestry technician, specifically the Harrachov Forestry Company. At that time, the foresters were liquidating a large wind calamity. During the next 35 years, he experienced many other calamities in the western Krkonoše Mountains caused by wind, insect pests and pollutants from Czech, Polish and East German power plants. In Harrachov, he worked as a technical and management officer, cultivation inspector, production deputy director, and after the forest company was transferred to the Krkonoše National Park, as director. He started a family in Harrachov. His son Jan was born in 1972, and his daughter Barbora in 1974. In the first half of the 1980s, he was offered to join the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. At first, he refused, then he accepted. He took part in the rescue of the western Krkonoše Mountains after the worst calamity, which hit the pollutant-weakened forests after a huge temperature break on the night of 31 December 1978 to 1 January 1979. Insect pests took over the affected forests. The calamity deprived the western Krkonoše Mountains of forests, especially at altitudes above 900 metres. At the beginning of the 1990s, Petr Kadleček was present at the restoration of the destroyed forests, which was made possible thanks to subsidies of CZK 375 million from the Dutch Face Foundation, represented by Miroslav Fanta, a former employee of the Krkonoše National Park and an emigrant. In 2004, Petr Kadleček was instrumental in establishing the Šindelka Museum of Forestry and Hunting in Harrachov. In 2024, he lived in Harrachov.