If you gave up your career when being young and childless, they had nothing to blackmail you for

Download image

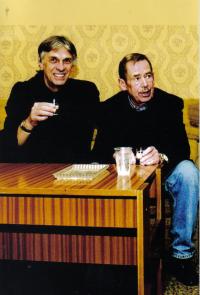

Peter Kalmus comes from a nationally mixed family. His father was an engineer of a Jewish-German descent and his mother was a Slovak, practicing evangelical religion. He spent his childhood in Piešťany. His parents got divorced and Peter doesn’t remember his father from his early childhood. In 1962 he moved to Košice. He met his father for the first time in summer of 1968, when they formed an activist-artistic installation together as a protest against the Soviet troops’ invasion of our territory. Peter Kalmus has been proceeding such civic activities until today. He studied at the Secondary Technical School of Transport in Košice and later he was an autodidact. He had various contacts with Prague underground and culture, which he closely monitored. He attended various forbidden concerts and exhibitions. Until present days he has been a very significant person of Slovak culture. He lives by turns in Košice and Piešťany and has no children.