Father Kavan shot Nazis. Son shot at the Communist Party by samizdat

Download image

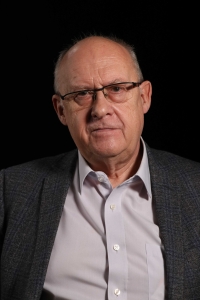

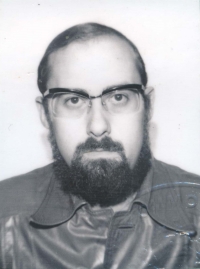

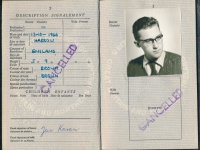

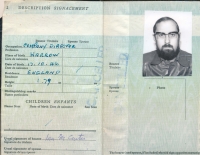

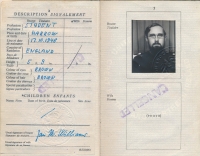

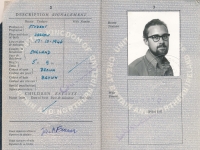

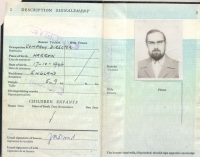

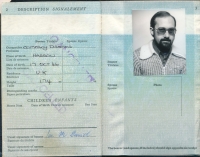

Jan Kavan was born on 17 October 1946 in London to Czechoslovak diplomat Pavel Kavan and his English wife Rosemary. Jan Kavan’s father fought as a Czechoslovak soldier alongside the Allies on the Western Front during World War II. From 1946 he worked as a diplomat at the Czechoslovak Embassy in the UK and was a convinced member of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ). He returned to his homeland in 1950 and was arrested by State Security (StB) in 1952 as a part of the staged trial of the anti-state centre headed by the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, Rudolf Slánský. Pavel Kavan was sentenced to 25 years in prison, and returned from there three years later, at Christmas 1955. The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia readmitted him to its ranks. However, due to his failing health, he died in 1960 at the age of only 43. Jan Kavan and his brother Pavel were brought up by their mother Rosemary, who came originally from England. Jan Kavan suffered from frequent illnesses as a child. After graduating from secondary school, he entered the Faculty of Education and Journalism at Charles University in the first half of the 1960s. In 1966 he joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. He thought that as a member of the party he would have easier access to archival materials from his father’s trial. However, he was soon expelled from the Communist Party. He worked in the leadership of the Union of University Students (SVS) with Jiří Müller and Luboš Holeček. At the time of the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops on 21 August 1968, he was at a student movement conference in Kansas City, USA. Because of the invasion, he was sought out by local journalists, wrote articles for newspapers and magazines and appeared on the radio. After the self-immolation of the student Jan Palach on 16 January 1969, Jan Kavan and other student leaders held talks with the Czech Prime Minister Stanislav Rázl. They arranged with him a media statement of the Union of University Students and the organisation of a rally to commemorate Jan Palach on the day of his funeral on 25 January 1969. In the spring of 1969, before travelling to Stockholm, security officers arrested him at Ruzyně airport and confiscated confidential Communist Party documents and foreign currency, of which he had bigger amount than the regulations of the time allowed. This was followed by an interrogation at State Security and the confiscation of his passport. In 1969, Jana Kavan got his passport back and travelled to the UK, where he remained until 1989. Since he was born in London, he immediately became a British citizen. In 1969 and 1970, the State Security kept a file on him under the code name Kato. In 1970 he began cooperating with the Czechoslovak anti-communist resistance to smuggle banned literature, magazines, reproduction equipment, cameras and film material into Czechoslovakia. Through him, samizdat literature or film footage of dissidents was smuggled out of the country to Western Europe. In 1970 he arrived in Czechoslovakia on a British passport with a changed surname, to meet Petr Pithart. In 1971 he founded the Palach Press agency, which offered subscribers from the world’s media news about the opposition movement in totalitarian Czechoslovakia. In the UK, he got a bachelor’s degree. In 1981, Czechoslovak customs officers stopped a camper van with samizdat literature smuggled from Czechoslovakia to Western Europe. State Security arrested dissidents in Czechoslovakia linked to the export and import of banned materials. It also detained two French couriers. Large demonstrations were held in France, Austria and other democratic countries in support of the arrested people. After three quarters of a year, Jan Kavan managed to resume secret shipments to Czechoslovakia and back. In the second half of the 1980s, he began working with Polish and Hungarian dissidents and published the East Europe Reporter. As a British citizen, he could fly easily to both Warsaw and Budapest. He also met Czech dissidents in Budapest. In 1987, he flew undercover to Prague and repeated his visits to representatives of the opposition movement. On 25 November 1989, when the Velvet Revolution was already underway in Czechoslovakia, he flew from London to Prague. Because of the dissident Jiřina Šiklová’s slip of tongue, State Security knew his British name and surname, detained him at Ruzyně airport and took him away for questioning. A few days later, another interrogation followed in State Security’s villa in Prague-Dejvice. State Security wanted information from Jan Kavan about what was going on in the centre of the Civic Forum, in Prague’s Špalíček. At the end of the interrogation, State Security agents and Jan Kavan toasted to better times. In the free elections in June 1990, Jan Kavan stood as a candidate for the Civic Forum. He succeeded and became a member of the House of People of the Federal Assembly. In 1991, reports surfaced that he had collaborated with State Security. He did not run in the 1992 elections because of suspected links with the former communist secret services. In 1993 he joined Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party. He decided to disprove the suspicion of cooperation with State Security in court, trial lasted from 1991 to 1996 and Jan Kavan came out victorious. In 1996 he was elected to the Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic for the Prostějov district. From 1998 to 2002 he was Minister of Foreign Affairs, and from 2002 to 2003 he was President of the United Nations General Assembly. From 2002 to 2006 he served in the Chamber of the Parliament of the Czech Republic. During his time as Foreign Minister, he faced suspicious cases - for example, the unfavourable lease of the Czech House in Moscow, the contents of the ministerial safe, and the prosecution of his secretary-general, Karel Srba, who was sent to prison by court for preparing the murder of journalist Sabina Slonková. In 2021, Jan Kavan was living in Prague, was divorced and had four children.