The concentration camps were always a topic in our family

Download image

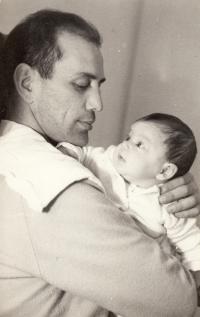

Judith Kellner-Tauberová was born on 11 May 1943 in Palestine. She lived with her mother in Nahariya and Haifa until she was three. Her father Hainz Jakob Tauber left to fight in the Czechoslovak Foreign Army. He was deployed at Tobruk and later participated in the second wave of the Allied invasion of Normandy. Several of Judith’s relatives died in concentration camps because they were Jews. In 1946 she and her mother joined her father in Czechoslovakia, where he was completing his university degree. When the Taubers wanted to emigrate to the newly established State of Israel a few years later, the Communists denied them passage. Her father worked as a doctor in Benešov nad Ploučnicí. In 1966 the witness graduated from the Faculty of Medicine of Charles University in Prague. She married an Israeli citizen, which also enabled her to leave the country. She worked in Israel as a pathologist for thirty years.