“Ours is a society without positive role models. Until that changes, the problems are here to stay.”

Download image

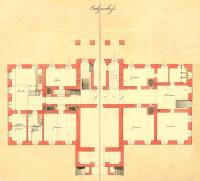

František Kinský, full name Maria František Jan Emanuel Sylvestr Alfons, Count Kinský of Vchynice and Tetov, is the descendant of an old aristocratic family. He was born in December 1947 in Hradec Králové, where his parents happened to be staying - although they normally lived in the village of Košeca in Slovakia. His father was the director of a local paint factory, and his mother was the factory’s main shareholder. After February 1948, his father continued to direct the factory, but he was soon placed on trial for fabricated political charges. He ended up spending several years in the Jáchymov uranium mines. František Kinský lived with his mother at his grandfather’s family estate in Kostelec nad Orlicí, but they were then forced to leave Kostelec, and so they moved to Prague. He attended a secondary technical school of construction. He applied to study journalism, but he did not complete his degree. During Prague Spring and the invasion of the Warsaw Pact armies in August 1968, he underwent compulsory military service, with the “road corps” (unarmed, practically non-military road workers - trans.). Upon his return he was employed at Czechoslovak Television; he then worked at a construction office of the Kovoprojekt enterprise. In 1980, he left the construction business and moved to the advertising firm Merkur, changing his focus to marketing. After 1989, he worked as the creative director of Ammirati Puris Lintas, and then in the same position at the multinational advertising agency Ogilvy & Mather. František Kinský is now an active businessman, the owner of the firm Písník Kinský, which mines sand from his family’s estate, and the one-third co-owner of Cihelny Kinský, a subsidiary of the Austrian concern Weinerberger. In 2004, he assumed responsibility for the family’s stately home in Kostelec nad Orlicí after his father. In 2010, he also began taking an active part in local politics in Kostelec nad Orlicí, where he lives.