I’m trying to make my mother’s name live in the hearts of people

Download image

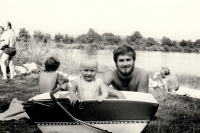

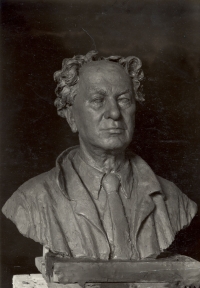

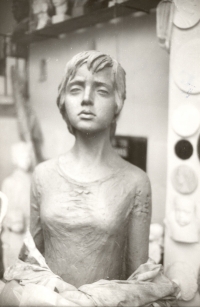

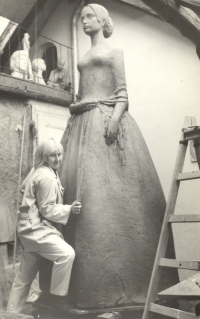

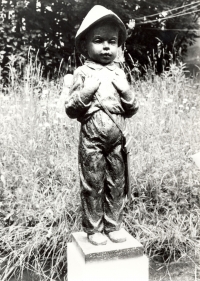

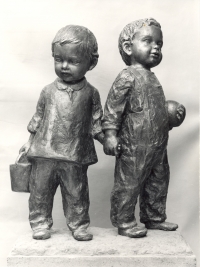

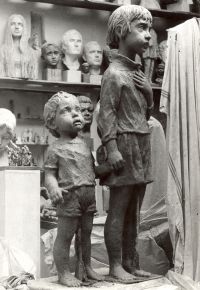

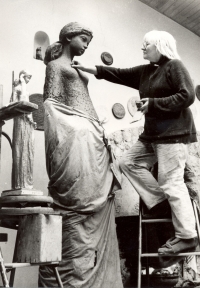

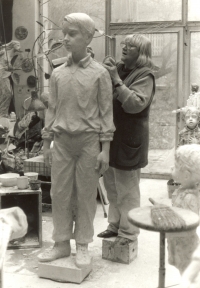

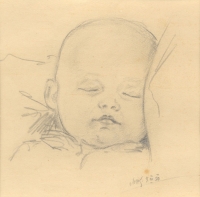

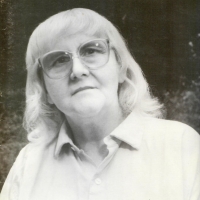

Sylvia Klánová was born July 31, 1949 in Pilsen. Her father František Kuča was born January 21, 1921 in Ostrava. He was a teacher of foreign languages and foreign language stenography. Her mother, the prominent academic sculptor Marie Uchytilová-Kučová, was born January 17, 1924 in Kralovice. From 1963 to 1967 Sylvia studied at Mikulášské gymnázium in Pilsen. In 1968 he completed a graduate course of French in Prague, where she also witnessed the August occupation. After that she graduated from a librarian school and later worked in the field of historical preservation. In 1970 she married Miroslav Klán. A substantial part of her life is closely connected to her mother’s lifelong work on the Lidice children sculpture. After her mother had passed away just one day prior to Velvet Revolution, Sylvia and her husband took care of the realization of the Memorial to the Children Victims of the War, Lidice. The sculptures were gradually brought together to the Lidice plain since 1995, until the sculptural group was completed in 2000. On October 28th, 2013 Sylvia received a state decoration for her mother on the Prague Castle – First Grade of the Medal of Merit in memoriam. In January 2007 she also received honorary citizenship of Lidice for her mother and honorary citizenship of the city of Pilsen in October 2018. To this day she holds lectures about her mother’s work and participates in all thematic events both in Lidice and elsewhere.

![Marie Uchytilová's daughter, Sylvia Klánová, by the sculptures (1980s]](https://www.memoryofnations.eu/sites/default/files/styles/witness_gallery/public/2019-04/04_3.jpg?itok=bp6QFI9l)