Trips outside Czechoslovakia were maybe one half of athletes’ motivation

Download image

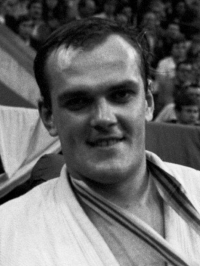

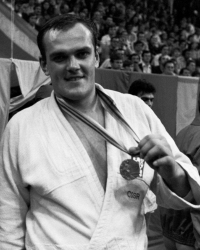

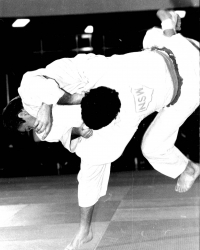

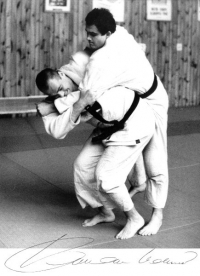

Vladimír Kocman was born April 5, 1956 in České Budějovice where he grew up together with his three brothers. As a kid he did sports in his free time, including hockey, soccer, bike riding or skating. He started doing judo in high school which he fell in love with and trained every free minute he had. Soon he got into the junior national team a started driving around competitions all over the world. He won the bronze medal at the Moscow 1980 Olympic Games. He prepared for the Los Angeles 1984 Summer Olympics but couldn’t attend it eventually (like many other sportsmen), due to the political conflict between the Communist Bloc and the West. Despite that he was able to travel many parts of the world only few could visit during the Communist times, such as his two-months long judo training in Japan. Even though he came from an atheist family, he found faith during his judo career which eventually led to the end of his professional sports career. He had to work as a boilerman until the Velvet Revolution in 1989. He started a sports supplies business in the 1990s. Today he is retired and leads a Christian parish.