My Lord, I am yours, do whatever you want with me

Download image

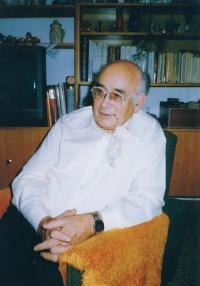

Pavel Konzal was born on December 31, 1927, in Prague as the sixth child of Antonín Konzal, the banking clerk of the Church credit union in Prague. The family was very religious. In 1939, Pavel joined the monastery of Svatá Hora near Příbram as a vocalist and an altar boys. After two years he switched into private grammar school of the Redemptorist Order in Libějovice, but his studies were interrupted by the Heydrichiade. In spring 1945 he was summoned by the Germans to dig trenches in Poland, but he and his whole group managed to flee at the end of the war. After the war, he entered the noviciate in Července near Litovel and he prepared himself for the life of a monk. He was living in a redemptorist convent in České Budějovice and, at the same time, studied the local classical grammar school. On April 13, 1950, he became a victim of the so-called police campaign K, a night raid on monasteries which were closed as a part of the destruction of churches. He was interned by the Secret Police in the monastery of Králíky which then served as a labour camp. In autumn 1950 he was sent for his military service to Komárno to Auxiliary Technical Battalion (PTP), where he served in the so-called Parson Platoon. On his return from the military service in 1954 he was banned, for political reasons, to complete his secondary education and, therefore, he could not study theology. He decided to become a lay priest and married. He joined the group helping the Catholic activist Zdeněk Cikler, who hid from the Secret Police for three years. In 1956, the members of the group were arrested. Pavel and his wife were sentenced to 3 and 2,5 years in prison. He served his sentence in Jáchymov mines, his wife Zdena in the labour camp Želiezovice. After several months they were released on amnesty. They were still active in Catholic circles, worked with the youth and when their son was born, their cottage became a meeting place for Catholic families. In their Prague flat, they accommodated visits from the West. They lived under the constant surveillance of the Secret Police. Pavel worked in ČKD as a worker, then served as the driver and worker in construction geology. Since 1987 he was the driver and assistant of the Prague bishop Antonín Liška. In 1989 he co-organised trips to Rome for the beatification of Anežka. After the 1989 revolution he served in the bishopric’s heritage department and for his long-term work for the church, he was awarded by the cardinal Dominik Duka.