There was no time for tears

Download image

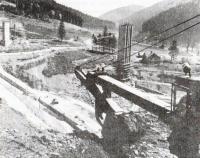

Julie Košťálová was born as Julia Chromcová on 19 May 1939 in her parents cottage in the settlement of Ružanec in the Beskid Mountains. The settlement nestled on the slopes of Mount Smrk (Czech for “Spruce”) above the valley of the River Ostravice. Her father was a forest worker in the archiepiscopal forests, her mother kept a small farm and had lived with the hardships of the mountains all her life. In November 1944, aged five, Julie Košťálová experienced a robbery undertaken by a group of armed men; the settlement never discovered if they were partisans or not. In 1950 the family started building a new timbered cottage in Ružanec, which they completed two years later. At the time, Julie Košťálová’s mother refused to join the Staré Hamry United Agricultural Cooperative, and to punish her the officials did not connect the settlement to the power grid. All the other secluded houses had electric lights, but not in Ružanec. In 1956 the Košťáls were told they would have to abandon their new cottage because the River Ostravice would be transformed by the construction of a dam and the creation of Šance (Czech for “Opportunity”) Reservoir. The witness was studying at the Secondary Medical School in Opava at the time, she graduated in 1957 and became a children’s nurse. In 1959 she married a gamekeeper, and in 1961 the family with children lived in the place called Šance, where builders were preparing what was to be the biggest gravity dam in Central Europe. The material for the dam was mined directly from the quarry at Šance. Julie Košťálová’s home was shaken by explosions, during the blast work she had to carry her children to a safe distance in her arms, with stones flying through the air and walls cracking. In 1964 the Košťáls were assigned a flat in a block of flats in Frýdlant nad Ostravicí, as were dozens of other mountain dwellers from the valley between Mount Smrk and Mount Lysá (Czech for “Bald”), whose houses were flooded by the reservoir in 1969. The witness worked as a children’s nurse her whole life, she visited the children in the settlements and secluded homes in the vicinity of Staré Hamry and Bílá, but her native settlement was destroyed during the construction of the dam and she herself has lived in an apartment house in Frýdlant nad Ostravicí for fifty years. She retired in 1993.