I won’t turn back in life, I have to keep looking forward

Download image

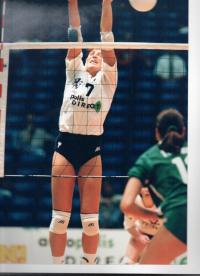

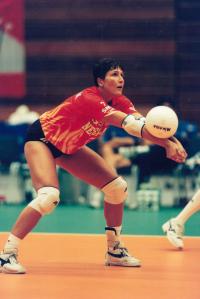

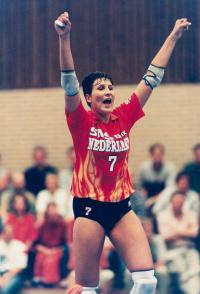

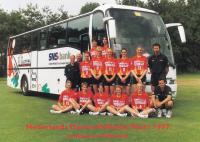

Irena Králová, née Machovčáková, was born on 13 November 1968 into a lawyer’s family in Prague. She grew up with her older sister and younger brother. Her parents introduced her to the game of voleyball, which has always played an crucial role in her life. When she was twelve she started playing for Red Star Prague, which signed her on as a great talent. She gradually fought her way into the national team. In 1988 she decided to emigrate, so she quit the national team during a friendly match in the Netherlands. Her parents officially disowned her to save their careers. Soon after she was accepted into the Dutch national team, with which she won a silver medal at the European championship in 1991 and a gold at the European championship in 1995. She took part in the Olympic Games in Barcelona and Atlanta. In 2011 she concluded her professional sports career and returned to the Czech Republic with her husband. She lives in Prague, she has two children, and she still plays voleyball.