They showed the occupiers what brotherhood is. And the Russian coach kicked the players

Download image

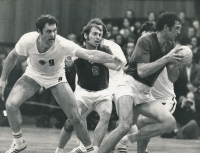

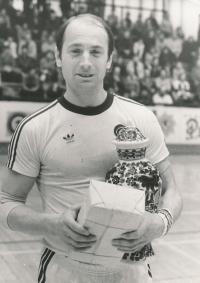

Jindřich Krepindl was born on 6 July 1948 in Št’áhlavy in the Pilsen region. He had two older brothers. His mother worked in the gardening at the castle, his father as a foundryman and workshop manager at the Škoda factory in Plzeň. When Jindřich Krepindl was twelve years old, his father died in a carbon monoxide leak at the Škoda factory. Jindřich Krepindl played handball from the age of eight, and second league in Št’áhlavy from the age of sixteen. He graduated from a mechanical engineering school and at the age of eighteen he made the junior national team. In July 1967 he joined Dukla Prague, where he played for two years in the same team as the world champions. On the twenty-first of August 1968, he experienced the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact troops in the Dukla barracks in Stadion Juliska. He and other army athletes took down street signs with names to confuse the occupiers. In 1969 he transferred to Škoda Plzeň, with which he won the national handball championship in 1974. In 1972 he won silver medals with the national team at the Summer Olympics in Munich. In the semi-finals they defeated the Soviet Union and returned the occupation of 1968 at least on the sports field. In 1974, he and the national team won sixth place at the World Championships and seventh place at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal. The witness studied coaching at Faculty of Physical Education and Sport of Charles University, and in 1983 went to train and play in Bad Neustadt, West Germany, where he spent three years. After 1989, he was manager of the Pilsen handball team, coached the national under-21 team, played and coached in the Federal Republic of Germany and had a sporting goods store in Pilsen. He and his wife raised two sons. In 2023 he lived in Třemošná.