Before the fall of Communism, he could not write novels on political or historical topics

Download image

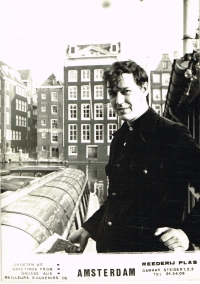

Lubomír Kubík, author of popular novels with political and historical themes, was born on the 4th of March in 1945. He spent his childhood in postwar Jihlava where most of the original, German-speaking inhabitants were expelled and replaced by newcomers. He came from a well to do family of clerks. After his studies, he also got a job in an administrative position but since his youth, he had been an active writer. He wrote adventure stories for young readers including scripts for graphic novels; his great inspiration was Jaroslav Foglar. In 1983, he married to Brno, he had met his wife in Moscow. He could express his interest in political and historical topics only after the fall of Communism in 1989. He has published many works on these themes since. The Communist régime limited his travelling, especially at the beginning of the 1970‘s when his passport was taken away from him. In 1974, he was questioned by the State Security. After the 1989 revolution, he became active in efforts to renew the autonomy of Moravia.