“How come that this shit has made me a man? So it’s not shit but literature.”

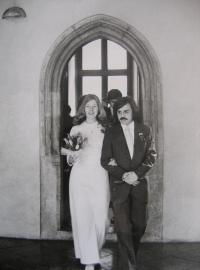

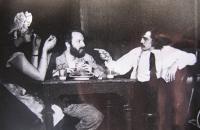

Erwin Kukuczka was born on May 27, 1944, in Istebné in Poland that was part of Germany at the time. As his mother was suffering from tuberculosis her son Erwin was taken away from her and was put in a German camp. Before he was separated from his mother, his father followed the advice of a nun and gave him the German name Erwin. He came back home to his father in 1946. His father afterwards told him that in the institute where he was placed with other 316 children, they were used as Guinea pigs for German experiments with artificial nutrition. Only twelve of those children had returned home. Since that time on Mr. Kukuczka has been having digestive problems throughout all of his life. He spent his youth in Jablunkov but it wasn’t a happy time for him. His stepmother was very hard towards the children and so Erwin started to run away from home. He also spent some time living with his aunt who was a devout catholic. That’s where he started to learn about faith and religion for the first time. At the age of thirteen, his step mother moved away and his father soon followed her to Třinec. He lived alone for a year and after he graduated from elementary school he started to study a vocational college in Třinec in the field of steel industry. He started to do a lot of sport at about that time - above all mountaineering. He also made a lot of friends who were interested in literature and the arts. In 1961 Erwin finished his professional training and was called up for military service. He started to work in the Třinec metal works in 1964 where he also met his father. After working three years for the works he was thrown out of his job for his appearance in a gathering of the staff of the works. He left to Prague where he became an actor in the cult theater Orfeus. The actor and producer Radim Vašinka showed him the world of the Prague bohème and introduced him to one of the most prominent figures of the so-called Prague “underground” (the non-conforming artists, writers, intellectuals and dissidents of the Communist regime - note by the translator) Egon Bondy. Their relationship developed into a life-long friendship that helped Erwin to orient himself in literature and also in philosophy. Kukuczka occupied himself more intensely with his poetry. He was also plagued by his personal hardships and feelings of loneliness and estrangement. These feelings gradually drove him into a mental asylum in Bohnice. One day before the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the armies of the Warsaw pact, he was celebrating his return from the asylum with his friends from the Orfeus theatre. In the morning, still under the influence of alcohol, he and Radim Vašinka set out to join the demonstrations against the foreign intervention. He was distributing some leaflets and was nearly arrested by Soviet soldiers. He was aided by his worker profession and the knowledge of the Russian language. With the advent of the Normalization in Czechoslovakia the position of his friend Bondy became untenable in Prague (he was identified as the intellectual originator of the revolution) and therefore they left to Jablunkov, where Bondy wrote his famous book Buddha on Erwin’s rectory. Bondy later also wrote his philosophical work The Shaman. Erwin Kukuczka’s person appears in that book as a real person. Kukuczka was meanwhile searching for the meaning of his life. Although his friends advised him to study acting or journalism, Bondy, who read his poems and discovered a deep-seated spiritualism in it, advised him to study theology. Therefore Erwin started to study the Jan Hus Czechoslovak theological faculty in Prague in 1969. His activities outside the school resulted in his expulsion from the school in 1970. He left to Svitavy where he worked as a manual worker and read. His lifelong love became - according to his own definition - the “holy trinity” of the writers Jakub Deml, František Bílek and Otokar Březina. He came to Prague to perform in Orfeus from time to time. After a year he returned to Prague and started to work in the mental asylum in Bohnice. This is when he started his Samizdat-publishing activities. He would copy and reproduce the works of prohibited authors like Seifert, Skácel, Mikulášek, Achmatovová, Bondy - to name just a few - during his night shifts in the asylum. Since the beginning of the seventies until today he’s been publishing his own and adopted works in an edition called LOUČ. In 1974 Erwin Kukuczka got married and followed his wife to a rectory in Hostinné, where he worked as a nurse. He began to publish in the official press - the CČSH, Czech Struggle or Blahoslav. Already in the middle of the sixties was he contributing to the Třinecký Hutník. Bondy stimulated him to translate the works of the Polish catholic poet Roman Brandsteatter. He also befriended Václav Havel and was invited for several of the notoriously known Hrádeček sessions. He mediated the first meeting of Bondy and Havel that took place in his rectory. The bishop Pochop of the Czechoslovak Hussite Church managed to get Kukuczka as a preacher into his parish. He seconded his wife in the religious community of Hostinné. He was transferred to Hlinsko by the bishop because of his contacts to people of the so-called “second culture” and the “underground” (the bishop was threatened with the loss of state approval for the providing of spiritual services). In 1982 Mr. Kukuczka and his wife moved to Ústí nad Orlicí where he became a preacher of the Czechoslovak Hussite Church in Žamberk and Nekoř. At the same time he was under surveillance of the secret intelligence services that started a file on him code-named “Kukačka” (cuckoo). Besides his own works he also published works by Škvorecký, Ladislav Klíma, Fischls interviews with Jan Masaryk etc. In the end of the eighties, Mr. Kukuczka was called upon by professor Salajka to finish his studies which he did. The time was right and so Mr. Kukuczka finished his theological studies and in 1989 he was ordained a priest in Žamberk. Since 1989 he’s been serving as a priest of the Czechoslovak Hussite Church in Žamberk and Nekoř. After the November events of 1989 he immediately got engaged and spoke out publicly on the orlickoústecké square. He also got engaged in the OF (Občanské fórum - civic forum, a political platform formed after the revolution - note by the translator). He was representing the city for two electoral terms. He regularly publishes his sermons in the regional press and organizes his “Soul Pilgrimage”. The first pilgrimage was dedicated to the multi-confessional personality of Přemysl Pitter. He still manages his edition that has grown to include new authors. The haste of the times and lack of time to devout himself to poetry has led him to occupy himself more with collage. Since 1995 he’s organized over ten exhibitions. According to his own words, his life has been most thoroughly influenced by faith and literature.