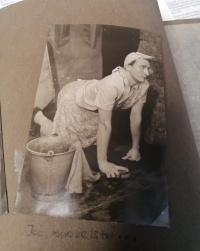

The suit from his father’s company changed to overalls

Download image

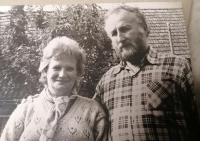

Miloš Kypta was born on the 25th of April 1931 in Prague to the family of the businessman Josef Kypta. His father ran a men’s fashion salon on Václavské náměstí at that time. At six years old Miloš had to fight against diphtheria for his life. He lived his childhood in the protectorate as a member of the 21st troop of the Club of Czech Touristsm which functioned on the principles of Scouting. After the war he studied at a business academy. The February coup d’état politically split the family left and right and his father’s company was nationalized. Miloš Kypta found himself a job in industry, so that he would not have to end up in the mines. He spent most of his professional life in the business Domácí potřeby [Home Necessities]. He was conscripted into mandatory service in the year 1952, he did support tasks and later became a driver. In the year 1957 he married Věra Johnová. Later the couple raised their son Tomáš and daughter Marcela. Shortly before the Velvet Revolution his Scouting brothers revived the 21st troop. At the beginning of the new millennium his family left Prague and moved to Újezd nad Lesy. Here the witness also lived at the time of the filming of the interview in autumn of the year 2022.