“Help and trust each other.”

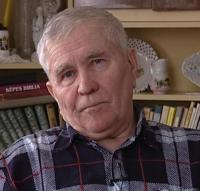

Ernest Kyrály was born on September 12, 1939, in the village of Zatín where he spent his entire childhood and a portion of his youth. He grew up in the peasant family, so in this respect he experienced the consequences of persecution even in his early childhood. Just because he had an unacceptable origin and sympathized with the peasants who were under his ward when he was in military service, he was investigated and redeployed to the Czech-German border area. There he had to participate in demolitions of houses that had previously belonged to the German population. After coming home he worked as a locksmith in Čierna nad Tisou. Together with his wife they resided in Veľké Kapušany. In 1968 he accepted the offer to make some extra money by carting the building material. He used his own truck. Nevertheless, he was persecuted by members of the National Security Corps (ZNB) and by the local authorities, so he was forced to sell his truck to the collective farm. Later on, he started working as a warehouseman in the gas warehouse in Streda nad Bodrogom where he witnessed the bribery and various frauds. He announced it to the enterprise executives but the result was that he alone was accused of overcharging the gas. Then, he was criminally prosecuted and charged with embezzling and he was also investigated very cruelly. He filed a complaint; however, it was a vain attempt as well as turning for aid to the President Gustáv Husák and to the Central Control Commission. Since the time he became unemployed, he wasn’t able to find any stable job. It meant that the whole family ended up in hopeless situation. He got over that hard period of time just thanks to the support from the side of his family.