It was a blessing in disguise, to run away from Hitler to Palestine

Download image

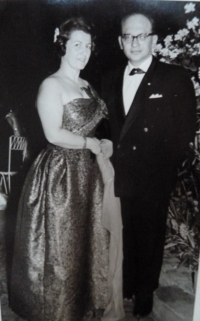

Edith Landesmann, née Stiassná, was born on January 5, 1926 in Brno to a Jewish family; her father, Karel Stiassný, was one of the founders of Maccabi in Brno, an international Jewish sports organisation, and had been serving as its chairman; he was a member of the B’nai B’rith lodge, he was a member of an education board, and most of all, he had been serving as a director of the Essler Textile Factory in Obřany. Her mother had a textile store and had been involved in WIZO (Women’s International Zionist Organization), a Zionist relief organisation. Both Edith and her older brother, Kurt, had been attending Czech-language Jewish schools. Their parents spoke German at home. After the German occupation of Mach 15, 1939, her father had been forced to leave his job, but later, he had been re-hired, as he had been found indispensable for the company´s operations. In August 1939, the family managed to leave for Palestine, where a subsidiary of the factory Karel Stiassný had been working in was being established. Karel Stiassny got a job as its director. Right from the start, her father got a job in Ramat Gan, near Tel Aviv. Edith found a new home in Palestine, she learned Hebrew fact and she went to school with local children. She trained as a seamstress. She wanted to live in a kibbutz, despite her parent’s wish, and one day, she would run away from home. She had been living in the Ramat David kibbutz for a year. In 1946, she married Robert Landesmanna, known as Bobby, who emigrated to Palestine from Vienna and was also a Zionist. They went to Brazil to visit his family, they also visited Paris and Brno. They were members of Haganah, an illegal Zionist military organisation, and they fought for the independent State of Israel. Back then, the witness had been working in the general staff in Ramat Gan, where she administered a database of Israeli soldiers. At the beginning of the 1950s, she moved to Vienna with her husband and her first-born son, Uriel, where her husband got a job at Panair do Brasil airways as its representative for Central and Eastern Europe. Edit gave birth to her second son, Michael. She settled down in Austria with her family, becoming a president of WIZO. In the 1980s, she also started working as a guide and a courier for foreign tourists. She accompanied them to many countries, working till her 76th birthday. At the time the interview had been recorded (2014), she and her husband were living in Maimonides Zentrum, a nursing home run by Vienna’s Jewish Community.