The war robbed me of my father and half my family, who were exiled to Germany

Download image

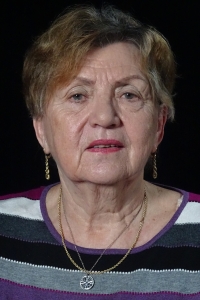

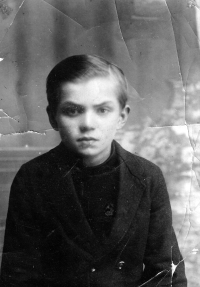

Ingeborg Larišová, née Kolková, was born on 5 March 1943 in Martina in the former Slovak state. Her mother was Czech from Ostrava, and her father was of German nationality. They both moved to Slovakia for work. Her mother trained as a hairdresser, and her father was a barber. Together they ran a barbershop and hairdressing salon in Vrútky, but it went bankrupt during the war. Her father then worked as a cashier in a German timber factory in Turany. During the Slovak National Uprising, the family split up. Ingeborg, her mother and her older sister left for the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. They spent the last few months before the liberation with relatives in Hradec Králové. Her father fled to Germany at the war’s end and died in a bombing raid. The rest of her father’s family was deported to Germany. Ingeborg lived with her mother and sister with her grandfather in the Ostrava colony of the Šalamoun mine. They were supported, among others, by their uncle Josef Tesla, who was a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and a minister in the cabinet of Antonín Zápotocký in the 1950s. Ingeborg graduated from grammar school and the civil engineering technical school. She worked at the Hutní projekt company in Ostrava until her retirement. In 2023, she lived in Ostrava.