The Velvet Revolution was a Festival of Freedom and our generation will never experience such a thing again

Download image

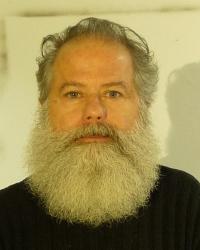

Štefan Lazorišák was born on October 25, 1959 in Košice. His father was an active communist and Stalinist, and his mother was a clerk. Štefan doesn’t remember his father, because when he was only two years old, his parents got divorced. Štefan had a six years older sister, who brought him to reading samizdat texts. During the grammar school studies, his sister invited him to spent summer in Prague, where he was fully enjoying the back then prohibited samizdat culture. This stay led him also to applying for Czech Technical University in Prague; however, in the end he didn’t finish his study. He was still searching texts for self-study of samizdats and other illicit literature. After the return to Košice he worked as a boilerman, workman, geodesist, scene-shifter and continued in his self-education. In the beginning of 1980s he began to publish his own literary attempts in magazine VOKNO. He was actively engaged in Košice independent culture. Štefan also became one of the founders of Košice Civic Forum and during the Velvet Revolution he co-organized conferences on crimes of communism. After the dissolution of Czechoslovakia he exchanged his public life for privacy and focused on his own literary work. Nowadays he lives and proceeds with his artistic work in Košice.