Mom never made a secret of her opinions

Download image

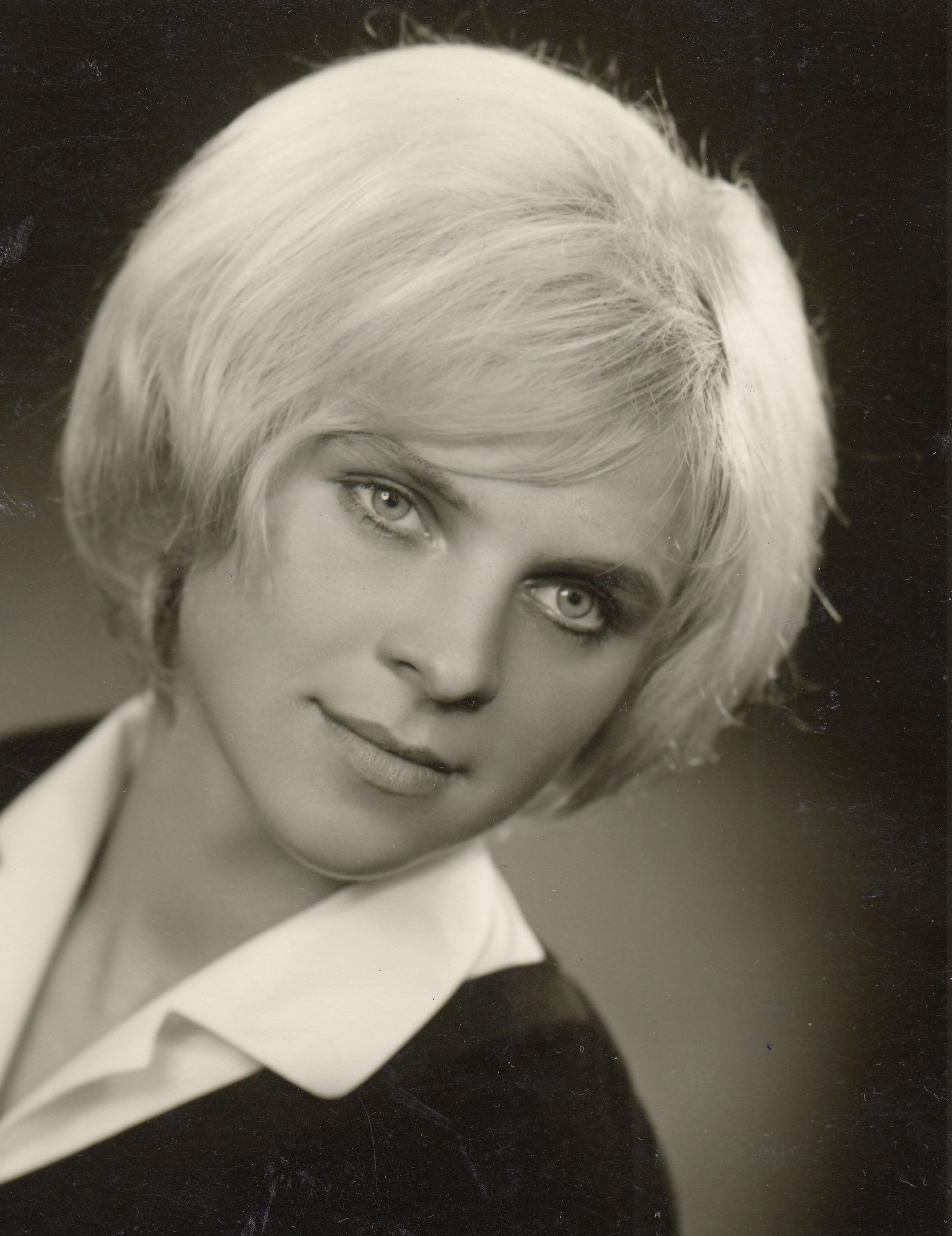

Jana Marková was born on 29 March 1947 to a teacher Maria Skalova, nee. Kopáčková, and the designer Jan Skála in Český Krumlov. Her mother spent her childhood in the small Sudeten village of Mezipotočí, from where they had to leave under dramatic circumstances after 1938. Despite everything her mother experienced before and during the war, she never stopped believing in the possibility of forgiveness. She was one of the few people who openly disagreed with the removal of the German population and considered it a fatal mistake. Her parents did not sympathize with the policies of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) and the emerging communist dictatorship. Marie Skálová made no secret of her views, which is why she taught only in small village classrooms, away from the limelight. She led her children to a similar mindset. In the 1960s, German friends who had been displaced from Mezipotočí after 1945 began to visit them. The year 1968 was one of the defining years of Jana Marková’s life. The arrival of Warsaw Pact troops shook her deeply. Like her parents, she took part in anti-occupation activities in České Budějovice. At this time, they were seriously considering emigration. After 1970, her mother was removed from the school system because of her publicly known opposition to the Communist Party. Through her friends from her studies, Marie Skálová became close to dissent and signed Charter 77 in June 1977. Jana Marková graduated from the Faculty of Education in České Budějovice in 1969. From 1976 she taught at the village school in Zahájí near Hluboká nad Vltavou. She never joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. After 1989 she became the headmistress of the primary school in Zahájí. In 2024 she lived with her husband Pavel Marek in Hluboká nad Vltavou.