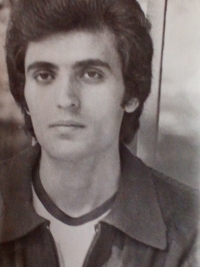

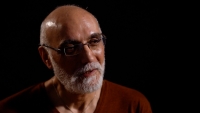

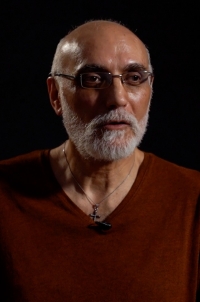

Poet, novelist, translator, essayist and scriptwriter

Download image

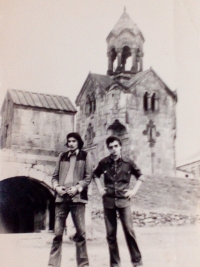

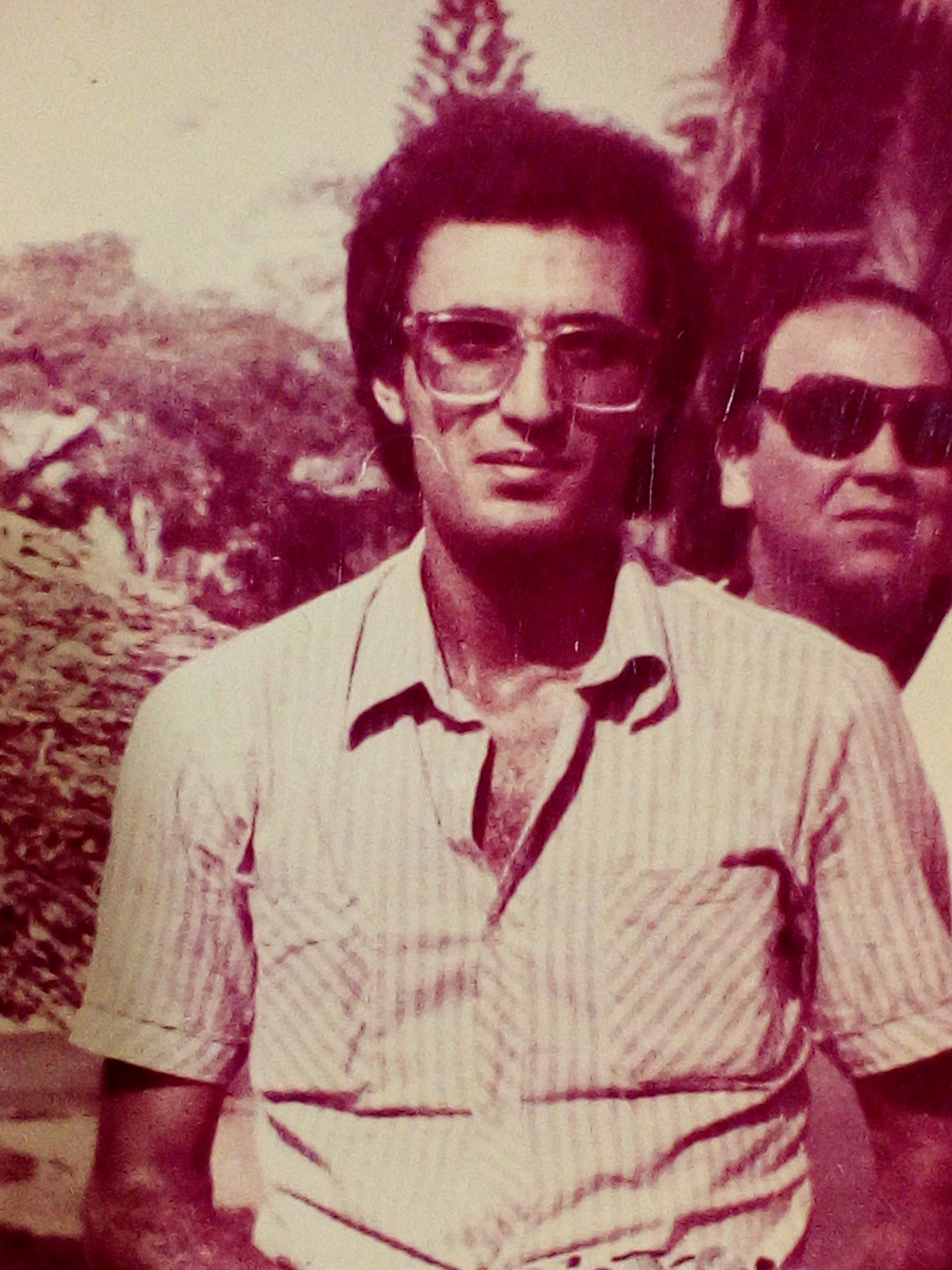

Vahram Martirosyan is an Armenian poet, novelist, essayist, translator and scriptwriter. He was born in 1959 in Leninakan (now Gyumri). He studied Armenian Philology at Yerevan State University (1976-1981), Psychology and Pedagogy at V. Brusov State Linguistic Institute (graduated its aspirantura in 1983), and defended a Ph.D. on the “Armenian Translation of Alexander Block” in 1986 at the Department of Russian Literature of Yerevan State University. In 2007-2008 he studied at Higher Courses of Screenwriters and Directors (Высшие курсы сценаристов и режиссёров) in Moscow. His first poems were published in 1975, the first book Emotional Diary appeared in 1988. His novel-anti-utopia Landslide (2000) was one of the rare bestsellers after the Independence, it was translated into several languages (Glissement de Terrain, France-Canada 2007, Оползни, Дружба народов, Moscow 2005 etc.). Martirosyan likes to change genres; he published a historical novel Hidings in the Name of the Cross about the period of Armenian Cilicia and the Crusaders, 2002, a political pamphlet Escape from The Land of Promise, 2004, a mystification The Cretin (L’Imbécile, Paris, 2010), a kind of mix of travel and love story novel Love in Moscow (2015), an adventure book about the young Soviet Armenian dissidents Cotton Walls (2019), an alternative history of Armenia Excavations from the Armenian History (2024). Martirosyan was cofounder and coeditor-of-chief of Bnagir, a magazine of the Armenian non-conformist writers (with the poet Violet Grigoryan, 2000-2006). Martirosyan translated Hungarian poets János Pilinszky György Petri and the novel of Nobel prize writer Imre Kertész Without Destiny.