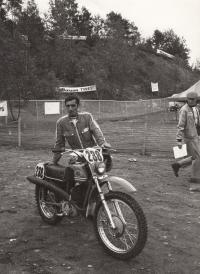

From training on unicycle to Hall of Fame of International Federation of Motocyclists

Download image

Květoslav Mašita was born on October 2, 1947, in Všenory near Prague. His mother, trained seamstress, took care of her son and a two-year-younger daughter, later worked in a factory. Květoslav loved racing from an early age. He and his friends raced on bikes, built tracks in a forest and when he received his Pioneer moped at fifteen he immediately started rebuilding it to a racing machine. His father, a clerk, could not help him with this work. So her read and tried to imitate what he could. At fifteen he took part in his first race and soon he became a member of the motorcycle association Svazarm in Dobřichovice. He was taken care of by his father’s friend Mr Hrudka, a brother-in-law of the motor legend Jaromír Čížek. He lent him, for a year, the bike Jawa 350 Europe and Květoslav did not disappoint him. He also helped him to be accepted into Dukla Benešov team where he started training properly and had his first racing season in 1966, which he concluded by six-day trial in Sweden. Since 1967 he was a member of the national team. The following summer was first in his ten-year triumphs in the European championship. In the six-day trials he won six times. He ended his career in 1979 and became a coach. In between 1982 and 1992 he was the head coach of Dukla Praha. On leaving Dukla he opened a motorcycle maintenance shop but his business was not successful. He retired soon and trained boys on quad bikes. He was awarded the highest possible prize in motorcycling, the silver medal for the development of motorcycling and in 2014 he was inducted into the Hall of Fame of the International Federation of Motorcyclists (FIM).