The entire family in jail

Download image

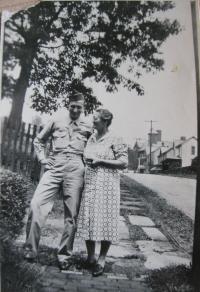

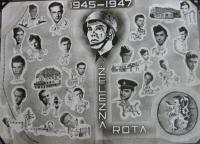

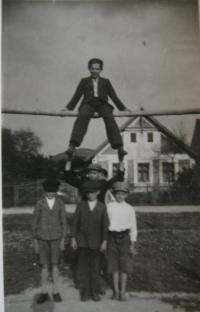

Jan Mastný was born on June 24, 1925, in the village Úboč in the region of Domažlicko. He came from farm No. 34, where his family had farmed since the 17th century. He graduated from agricultural school in Klatovy and higher agricultural cooperative school in Prague. He lived to the age of 14 in his native village and then lived in private apartments. After the war, he found employment in the Smíchovsko-Zbraslavské družstvo cooperative in Prague. After he completed his compulsory military service, he worked in the construction sector, taking part in construction work in the Ruzyně prison. In March 1952, the State Police arrested his parents and the two older brothers, followed by the arrest of Jan himself in April. In July 1952, the Domažlice district court sentenced him to three years in prison and the forfeiture of all property for the crime of sedition against the Republic, which he had committed by listening to Western radio in the presence of his parents. He served his term in the Prokop and Ležnice camps in Hornoslavkovsko. In 1954, he was conditionally released during an amnesty. His relatives were sentenced for alleged crimes of sabotage, illegal possession of arms and the plotting and sedition against the Republic. They were sentenced to 10 years in prison (his father), 8 years in prison (his mother). His brother, Josef Vojtěch, was sentenced to 8 years in prison and his brother Václav to 10 years in prison. After his release, Jan worked as a driver at the company Posista road and railroad construction, and since 1958 in a agglomerating plant in Ejpovice. After the plant had stopped its operation, he was transferred to the production of hot-air dryers, where he worked until his retirement in 1985.