It took away my brother

Download image

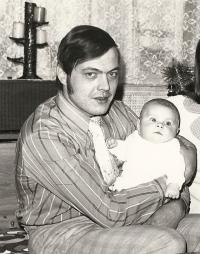

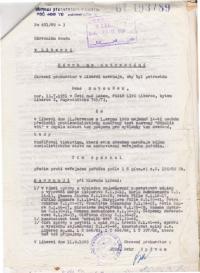

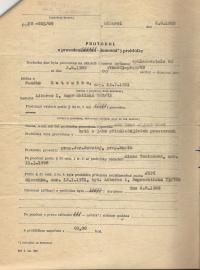

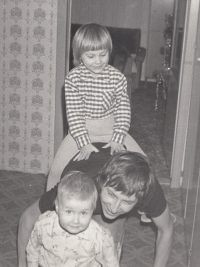

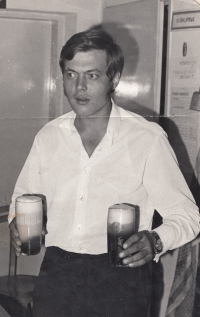

Jiří Matoušek was born on April 20, 1961 in Ústí nad Labem and a great part of his life is intertwined with the life of his stepbrother. His stepbrother René Matoušek, who attempted to emigrate in 1969 and spent several months in prison as a result thereof, was later imprisoned for disseminating pamphlets in support of the Polish Solidarity and on 17th November 1989 he was tried for distributing the petition ‘A Few Sentences.’ Jiří was visiting his brother in prison and he tried to support him as much as possible, such as by trying to get him a lawyer or supporting his family financially. Jiří himself faced troubles when searching for a job and he refused to join the Revolutionary Trade Union Movement (ROH) in spite of a career advancement promise if he did so. He signed Charter 77 in the 1980s and he maintained contacts with Prague dissidents.