What was I worth that day?

Download image

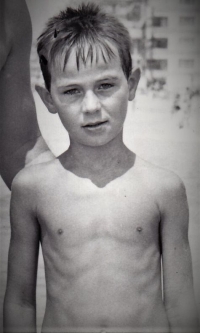

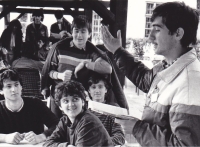

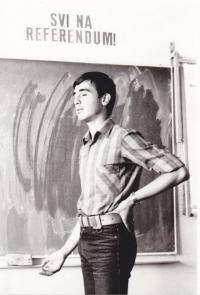

Hadis Medenčević was born in Derventa, Bosnia and Herzegovina, which was then part of Yugoslavia, on 16 May 1968. His father Ismet was a turner by profession, and his mother Alija was an ethnic Turk from Macedonia and worked as an accountant. Hadis and his older brother Suleiman were brought up in the Muslim faith. Hadis Medenčević graduated from a high school of electrical engineering and continued his studies at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering in Sarajevo in 1988. He did not finish college because his country was drawn into the maelstrom of war during the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1992. In 1992 he managed to leave for Czechoslovakia and settle in Prague. Hadis Medenčević has held various jobs and is now a computer scientist and business consultant. He is married and has two sons. He is an active member of the Prague-based Lastavica association which fosters the cultural traditions of the South Slavic nations and deepens reciprocity with the Czech Republic. He described his life in his novel “Blood, Honey and Hops”, which was published in Czech in 2021.