Hey you, don’t be afraid. Say it for us. We are not allowed to

Download image

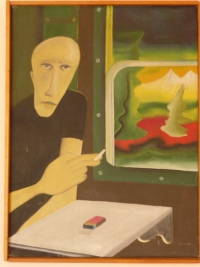

Vladimír Merta was born January 20th 1946 in Prague. He was one of the stars of folk music during the normalization era. Together with other folk singers (like Karel Kryl, Jaroslav Hutka and Vlastimil Třešňák), for thousands of people he became a symbol of resistance against the communist regime. His father Augustin Merta, whose memories are also accessible on the Memory of Nation portal, was a WWII veteran from the Western front. Merta claims that his vision is that of film, but that he expresses it in song. During the more liberal era of the late 1960s he was staying in Western Europe for some time. He studied two universities - architecture at Czech Technical University and film and television screenwriting and direction at the Film Academy. From the 1970s he had public appearances as a folk singer. He was holding three to four concerts per month for tens of people. In 1972 he co-founded a free artistic association Šafrán (Saffron). In 1977 the State Secret Police disbanded the association. But while the a joint LP record by Šafrán was banned and the complete release was destroyed on the StB´s order, Vladimír Merta did manage to release his solo record at the end of the 1970s. In a somewhat released atmosphere of the second half of the 1980s, when “going for folk” became a mass expression of public stance, Vladimír Merta was one of the most popular, but also one of the bravest persons, and one of the most inventive as a folk musician. Apart from his career as a singer he was active in other fields as well - he attempted his own film projects, he wrote the screenplay for a full-length film Opera ve vinici (Opera in the vineyard), he directed Čas her (Time of games) and Krajiny duše, krajiny těl (Landscapes of soul, landscapes of bodies). When he was prohibited from public performances, he played in the Viola Theatre or assisted director Pistorius in the Realistic Theatre. For over twenty years he also performed with the family band Mishpacha, which interprets Jewish folk music. In November 1989 he attended organizational meetings in the Realistic Theatre and in Činoherní klub, and from the balcony of Melantrich in Prague he sang for hundreds of thousands demonstrators. He thus became one of the protagonists of the fall of the Iron Curtain in Czechoslovakia. After 1990, folk singers tried to renew the activity of Šafrán, but the project was troubled with disputes and it did not succeed. Vladimír Merta founded his own music label and book publishing company ARTeM. He performed with singer Jana Lewitová. He taught culturology at Charles University and film music at the Film Academy. He continues to write screenplays and directs documentary films.