How well the communists managed to manipulate people and turn them one against another!

Download image

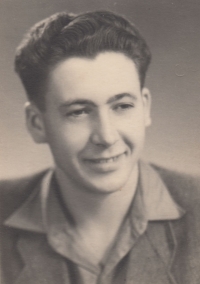

Cyril Michalica was born on St. Nicolas Day in 1933 in Kostice in the Břeclav region as the youngest of three children. His father was a Catholic and a progressive farmer who was actively involved in the life in the village. Young Cyril was helping the family during WWII, such as watching the surroundings of their house when men from the villages were gathering in Mr. Michalica’s house to listen to foreign radio broadcast. While in Kostice, Cyril experienced the fighting between Germans and partisans and the Soviet army, as well as the final liberation. His father established a machinery cooperative thanks to assistance from UNRRA after the war in order to speed up the recovery of local economy. After the coup d’état in February 1948, communists began with intense enforcement of the collectivization process, and Mr. Michalica, who refused to join the Communist Party, had all his agricultural machinery confiscated and he was prescribed unrealistically high delivery quotas, which led to the family’s critical financial situation. Mr. Michalica knew Mr. Gajda, who was guiding people across the border to Austria at that time, and he himself was helping to organize the border crossings. Cyril Michalica attended a church school in Velehrad, and when the monks were arrested, he continued his studies at the Secondary School of Viticulture in Mikulov. He was a member of Orel (Catholic youth sports organization - transl.’s note), and after February 1948 when their organization became disbanded, he and his friends continued meeting secretly and organizing minor acts of sabotage as a sign of support to farmers who were refusing to join the Unified Agricultural Cooperatives. In August 1950 they decided to set a cooperative’s haystack on fire. Their activity was found out and although Cyril Michalica was just watching, he was the only one of the perpetrators who was sentenced to three years of imprisonment. The other friend was still underage at that time, and the third one got away with a suspended sentence thanks to his favourable personal profile. Cyril’s father was sentenced to one year of imprisonment for his assistance in guiding people over the border. Cyril Michalica was imprisoned in harsh conditions of the corrective detention facility for young delinquents in Zámrsk, but he was released in amnesty a couple of months before completing his term. Upon his release from prison he had to do his military service in the Auxiliary Technical Battalion. He was eventually allowed to leave this unit due to poor health, but he had problems searching for a job. He was earning his living as a labourer and miner in coal mines in the Ostrava region, as a tractor driver, and wherever he worked, he was branded as a class enemy. After 1989 he sought rehabilitation from the court, but his petition was turned down by the Supreme Court, although the Court admitted that his act deserved recognition. The original sentence thus remained valid.