My sister and I promised each other we wouldn’t give in to the communists and be famous

Download image

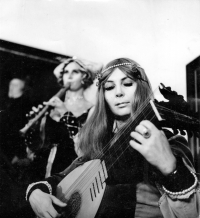

Eva Mikešová, née Matějková, was born on 26 May 1937 in Pardubice. She grew up in Heřmanův Městec near Chrudim. Her father owned a thriving steam sawmill with twenty-five employees. After February 1948, the communists nationalized the company and drove them out of the family villa. From 1952 the family lived in Mariánské Lázně. The father worked in timber factories, the mother worked as a maid. The witness was accompanied by a bad report card, because of which she was not allowed to study at university. She graduated from the Prague Conservatory in guitar. She taught at a music school in Mariánské Lázně. The school management persecuted them for alleged religious propaganda. Her sister Ludmila Seefried Matějková left for West Berlin on a scholarship in 1968 and stayed there. From the 1970s, Eva Mikešová made her living as a freelance artist. She played the lute and recorder, and devoted herself to the interpretation of Baroque and Renaissance music. She has performed with the Collegium Flauto Dolce throughout Europe. In 2023 she lived with her husband in Mariánské Lázně.