Většina lidí, co dělali počítače, byli mými žáky

Download image

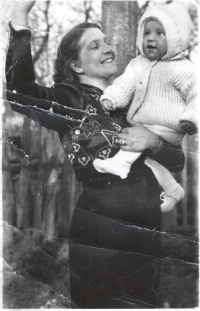

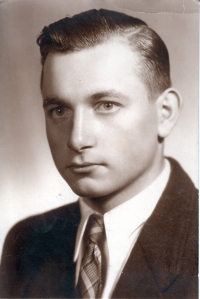

Jiří Mikuláš was born on August 2, 1930 in Prague into a family with strong Sokol traditions. His mother Božena and both sisters Zlaťa and Jarmila were Sokol’s devoted trainers and organizers, and Jiří worked in the Radio Department of the Czech Sokol Community during the All-Sokol meeting in 1948. In the final days of the war, the Germans almost shot him twice. From an early age, he was interested in how things are constructed and technically executed: he graduated from the Faculty of Electrical Engineering of the Czech Technical University in Prague and, by coincidence, after graduation, started working as an assistant at the newly opened Railway University. When the school moved to Žilina, he stayed in Prague and continued his teaching at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering of the Czech Technical University. At that time, he became interested in computers, he worked on the Soviet URAL1 and co-translated two books on computers from Russian. Several times the party’s district committee wanted to dismiss him from school, one of the reasons being his sister’s emigration in 1948. In the early 1960s, he managed to get a job at the national company Kancelářské stroje n. p. (Office Machinery Company), where he had the opportunity to delve deeper into computer technology. He attended professional training in England twice, in addition to France and the USSR. He became a leading expert, among other things he reprogrammed the Elliott computer software into Czech, including diacritics. During normalization, he again had problems with the regime, but as an expert in teaching the function and use of computers, he could eventually lead courses for students and the public. He was active in the field of computer technology until late age.