She wasn’t even fifteen and she helped save lots of lives

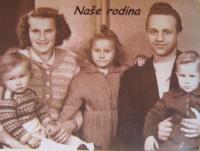

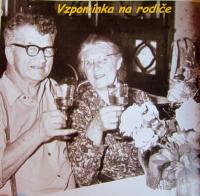

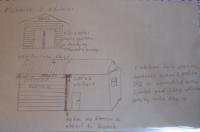

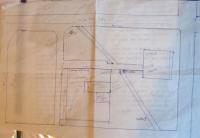

Dana Milatová, née Gajdošíková, was born in Želechovice nad Dřevnicí on 25 August 1929. In 1932 her father, František Gajdošík, was made administrator of the newly-established forest cemetery in Zlín. The family then moved to the cemetery building. Shortly before the war František Gajdošík had several hide-outs built in the house, the morgue, and the outhouses of the forest cemetery. He used them to hide durable rations and military material. He joined the resistance organisation Defence of the Nation. In early February 1943 Dana’s father was arrested. Already as a fourteen-year-old, Dana helped smuggle messages from her father in the Zlín prison. The information they contained saved the lives of many people. Later she became an important messenger for the 1st Czechoslovak Partisan Brigade of Jan Žižka (a famous historical Czech warrior - transl.), which was active around Zlín. Not only did she pass on information to the partisans, but she also helped supply them with food and even with weapons. She constantly put her life at risk. Several of her relatives joined the resistance. One of her uncles, Josef Gajdošík (Kopanský), was the commander of a group of partisans. Another uncle and aunt, Petr and Františka Gajdošík, died in the Mauthausen concentration camp. They also imprisoned the witness’s mother, Ludmila Gajdošíková, and her father was actually imprisoned twice during the war. He only survived due to lucky coincidence. But the liberation that came after the war did not bring much improvement to the family’s suffering. After the Communists came to power, her father and brother Otakar were arrested. They released them soon after, but her brother, weak from tuberculosis, died several days later due to the hypothermia he had suffered from while in remand. In 1950 Dana Milatová gave up her Communist party membership in protest, causing her to be labelled an undesirable person for the following decades.