Mr Mišík, you are always taking a chance. That might not pay off for you.

Download image

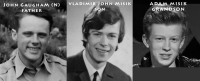

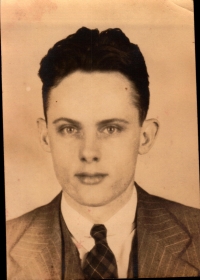

Vladimír Jan Mišík was born on 8 March 1947 in Prague to Alžbeta Mišíková, who was originally from Slovakia. His father was American soldier and transport pilot John Gaughan, whom Alžběta met after the war in Germany. He grew up with his mother as an only child and never knew his father. In 1964, he trained as an artistic carpenter at the Barrandov film studios, but his whole life he made a living from music, which greatly influenced the art scene between the 1960s and 1980s. During his apprenticeship years he started to play with the band Uragán and then performed professionally with the band The Matadors. In 1968, he co-founded Blue Effect, and after being fired from the band, he started playing in Flamengo. With this band he released the iconic album Kuře v hodinkách (Chicken in the Clock) based on poems by Josef Kainar. In 1974 he founded the band Etc..., with which he still plays today. In 1977, he refused to sign the Anticharter, and a few years later, in 1982, he was banned from public performance for screening a friend’s student film at a concert in Lucerna without permission. In the film the witness as the protagonist pointed out the hopelessness of normalization. At the time of the ban, he was offered to cooperate with State Security, which he refused. He was allowed to play again from 1984 on the condition that he would play at a festival of political songs in Sokolov. In November 1989 he supported striking students, sang at the demonstration on Letná Plain and supported the Civic Forum (OF) in North Bohemia. In 1990, he was elected as a deputy for the Civic Forum in the Czech National Council (ČNR). In 2016, during filming the movie Let Mišík Sing (Nechte zpívat Mišíka), he learned who his father, whom he had never known, was, and he met his still-living American siblings, of whom he had had no idea until then. He has three children and is married to his wife Eva.