Father felt like a second-class citizen, yet he had a home here

Download image

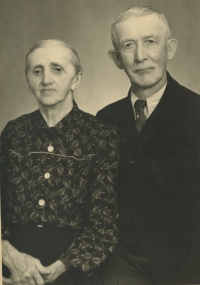

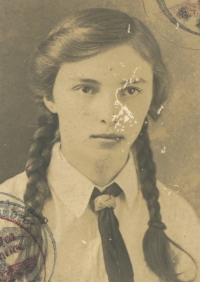

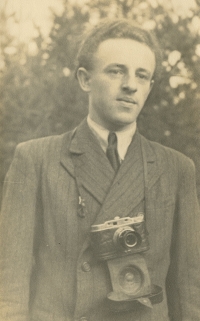

Erna Munzarová was born on 6 January 1928 in Chvaleč near Trutnov to Czech mother Anežka and German father Ernst Demuth. Her father had to go to the front in 1943, suffered injury and after the end of the war he ended up in a prison camp in Potsdam. Even though her mother had a German citizenship too, they did not have to be expelled as a mixed marriage. But all the relatives from her father’s side were expelled, including his old parents. Her father came back from captivity in summer 1945. Because Erna had to take part in conscripted labour, she joined the Šormovi family in Studenec as a helper in a household. After two years she returned to her parents who lived in Rudník. She worked with them in the factory. In 1948 she met her future husband Vlastimil Munzar, married him in 1951 and a year later their daughter Hana was born. They moved into a house left behind by the expelled Germans in Rudník, in the part called Terezín. They lived their whole lives in this house and their German relatives and friends, who were displaced after the war, visited them here. At the end of September 2021 Vlastimil Munzar died after a short illness, so he and Erna did not celebrate their seventieth wedding anniversary, which was in October that year. Erna Munzar lived in a house in Rudník with her granddaughter and her family in early 2022.