Marianské Lázně was like a revelation for me

Download image

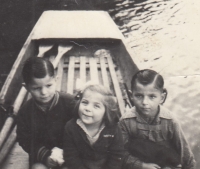

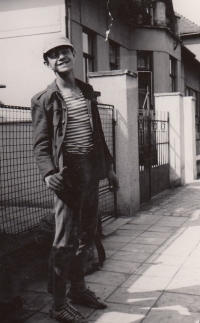

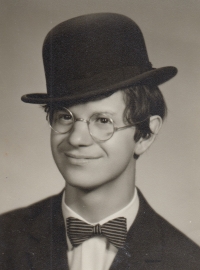

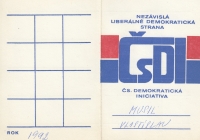

Vlastislav Musil was born on 4 May 1951 in Brno. He grew up with his two siblings in the Žabovřesky district of Brno and later in Staré Brno. His father František worked in the Brno Armoury during the war and his mother was a nurse. In 1966, he entered the grammar school, where he experienced the period of political relaxation of the 1960s. During the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops in August 1968, he was involved in anti-occupation activities. In January 1969, he took part in the march from Brno to Prague for the funeral of Jan Palach. After graduating from high school in 1969, he decided to pursue a career in gastronomy. He started his apprenticeship as a waiter at the Slavia Hotel in Brno and then graduated from the prestigious hotel school in Mariánské Lázně (1971-1973). In 1973-1975 he completed basic military service at the air defence unit in Lažany near Chomutov, where he encountered brutal bullying. After returning from the army, he rejoined the Krakonoš Hotel in Mariánské Lázně as a head waiter. His career continued at the Atlantic Hotel, where he worked as head of the service centre, and in the second half of the 1980s he taught professional subjects at the hotel school he himself had graduated from. In 1989 he joined the Democratic Initiative, later renamed the Liberal Democratic Party. In 1990 he was elected to the Mariánské lázně City Council and participated in many regional activities. He was involved in the founding of a branch of the humanitarian Lions Club, the Euroregion Egrensis for cross-border cooperation and the Association of Spa Organisations and Towns. In 1992, he joined the Excelsior Hotel as deputy manager and eventually became its director, a position he held until his retirement in 2015.