The spruces were yellow like tobacco. And the Krkonoše streams were dead

Download image

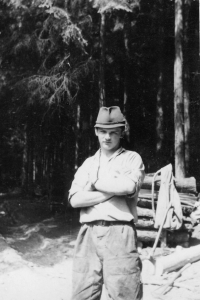

Václav Myslivec was born on 8th December 1949 in Cimbál near Semily. His parents raised two more sons, their sister died shortly after birth. The fate of the family was tragically marked by the First World War. Václav’s paternal grandfather, František, was killed in 1917 on the Italian front, and his maternal grandfather, Jaroslav Mašek, suffered a severe hand injury on the Italian front but survived the war. Václav Myslivec graduated from primary school in Semily, and after that, he entered a two-year forestry apprenticeship in Lomnice nad Popelkou. After a year’s work experience at a forestry company, he graduated from a two-year master forestry school in Šluknov, North Bohemia. He served his military service from 1970 to 1972 in the Slovak towns of Kežmarok and Michalovce, in Karlovy Vary, in the training area of Doupovské hory and in Stružná near Karlovy Vary. After retiring to civilian life, he worked at the East Bohemian State Forests. From the Malá Skála Forest, he moved to the Vítkovice forest in the Krkonoše Mountains and then to the mining centre in Harrachov. From 1978 to 1990, he dealt with the effects of an ecological disaster in the western Krkonoše Mountains, during which spruce forests died mainly at an altitude of 800 to 1000 metres above sea level due to exhalations from thermal power plants. However, the trees were dying even at 700 metres, and the forest soil was affected by acid rain caused by sulphur oxides entering the air from power station chimneys in the Czech, Polish and East German border areas. The physically and mentally exhausting work in the destroyed landscape caused Václav Myslivec health problems. Because of his young son, who suffered from severe asthma in the polluted air of the higher parts of the Krkonoše Mountains, Václav Myslivec’s family had to move from Vítkovice to the lower-lying town of Jilemnice. After the fall of the communist regime at the end of 1989, significant changes took place in the forestry industry. In 1997, Václav Myslivec quit his job at the abolished Harrachov Forestry Company, but he continued working for the Forests of the Czech Republic. In 2012, he left his position as a forester and retired. In 2023, he lived in Mříčná near Jilemnice. He and his wife raised a daughter and a son.