Svoboda v demokracii neznamená jen vyjet si, kam chceme

Download image

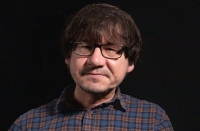

Václav Němec was born on the 5th of May in 1969 in Karlovy Vary. During the 1980’s, when he studied at the high school, he joined the local underground culture, started going to church and got to know the Catholic priests in the area who were persecuted by the Communist regime. After having graduated from high school, he held several short-term jobs between, 1988 – 1900, he served in the army, partly as a… in the marching band under the command of the Slané division under colonel Zbytek. In the 1990, he studied philosophy at the Faculty of Arts at the Charles University in Prague, he spent several years studying in Germany, he got a Ph. D. in history of Philosophy. He worked at the College of Karlovy Vary, at the Institute of Philosophy of the Academy of Sciences, at the Palacký University in Olomouc, at the University of West Bohemia in Plzeň and at the Faculty of Arts of the Charles University in Prague. He has been participating in public life, he is a member of many groups that criticise corruption and politicians getting involved with organised crime, such as the November Proclamation (We don‘t want to get used to Communists) ////