I can’t say something I don’t consider true, because then I couldn’t profess my values

Download image

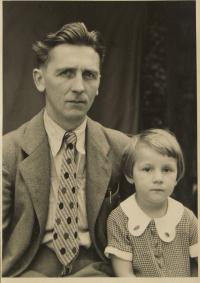

Eva Osvaldová was born on 9 July 1932 in České Budějovice, to Josef and Běla Rosenfelder. Her father was a veteran of the Russian front of World War I, a Sokol sports trainer, and the descendant of the old draper’s family of Rosenfelders, he had a fabric shop in Netolice. Eva’s mother came from the respected Netolice family of Toušeks, upon marrying she gave up her teaching profession and managed the shop together with her husband; they had two daughters, Eva and Marie, who was five years the elder. On 2 July 1942 the Gestapo arrested Josef Rosenfelder, and he executed in Tábor that very day. The family was terrorised by house raids, interrogations, and confiscation of property for another six months. Half of the family property, the house, and the proceeds of their business were given to a German administrator. After the war Eva completed a two-year course at the Social Medical School in Písek. In 1948 she participated as a young trainee in the 11th All-Sokol Rally in Prague. In the early 1950s their family fabric shop was nationalised. Together with seven other classmates, Eva was barred from taking her graduation exams at the Pedagogics Grammar School in Prachatice in 1951. She worked in agriculture, in production, and finally found a place in the District Institute for National Health. She was allowed to pass her graduation exams the following year, but she definitively lost any chance of studying at university when she refused to join the Socialist Youth Union. She then worked as a carer at schools in Písek and Tábor. In 1958 she married Zdeněk Osvald. After maternity leave she worked at a nursery school in Netolice, and she later headed a nursery school in Němčice, staying in that position until her retirement in 1988.