Don’t do anything that you don’t like to anyone else

Download image

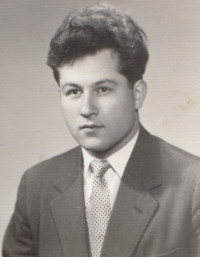

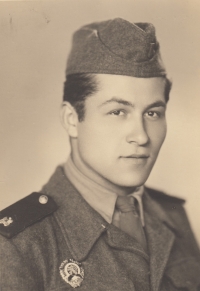

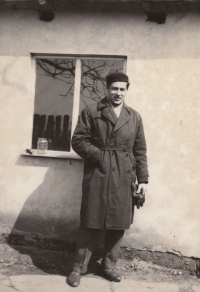

Viliam Otiepka was born on January 13, 1935 in the settlement Lubina pod Javorinou on the Moravian-Slovak border. His parents had a farm, all four sons had to help at home since their childhood. During the war, especially after the end of the SNP (Slovak National Uprising), parents supported the partisans, who left after the defeat of the SNP to the difficult-to-access mountainous terrain of western Slovakia. In the 1950s, his father was forced by the local communists to join the JZD (unified agricultural cooperative). At the age of fifteen, Viliam left home to train in Bratislava as a boatman for the Danube Cruise. He received the so-called livre de batterie, a passport that entitled him to sail in all the countries through which the Danube flows, including the so-called capitalist ones. He got to know new regions and cultures, but he was not satisfied with a certain limitation: even after work, he could only transport by boat. After completing his mandatory military service in Milovice-Mladé, he decided to change jobs: he obtained a driver’s license and since then throughout his active working life he was employed as a driver in various companies, for example in Pozemní stavby Olomouc and in Feron. He built a house with his own help in Uherské Hradiště, where he lived with his family even during the filming. In 2023, he and his wife will celebrate sixty-five years of life together. He retired in 1995.