Boys with machine guns came to the battalion. They wanted to shoot their way into Germany

Download image

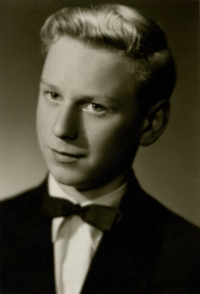

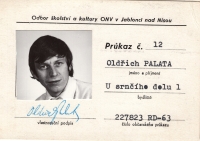

Oldřich Palata was born on 16 April 1943 in Čáslav. His mother Marie Palata was a saleswoman, and his father Bohuslav Palata worked as a surveyor. At the end of the Second World War, he, his mother, grandmother, and four years older sister were hiding in the underground of their family home. After the war, they moved to Jablonec nad Nisou, where his father got a job as a surveyor. He spent all his holidays with his grandmother and aunt in Čáslav. He successfully graduated from an eleven-year school. During his studies, he and his classmates collectively enrolled in the Czechoslovak Youth Union, but he was expelled from the union for the ostentatious non-payment of fees. He worked manually in an automobile brake shop for a year to improve his class profile and was admitted to college. He decided to study the history of art and aesthetics at Charles University. He spent the year 1968 in Železná Ruda in the Border Guard. After college, he joined the District National Committee in Jablonec nad Nisou as a methodist and later as an inspector of culture. After the political screening in 1971, he worked for a year in the yard crew of the Maják production cooperative. From 1972 until the time of the recording in 2023, he worked at the North Bohemian Museum in Liberec as a curator. While working, he completed a postgraduate degree in historical applied art and museology at Charles University. As a curator, he has prepared a large number of exhibitions in the Czech Republic and abroad. He had close friendships with many artists. He and his wife raised one son. In 2023, Oldřich Palata lived in Jablonec na Nisou.