Light up your cigarette, it’s going to be fine

Download image

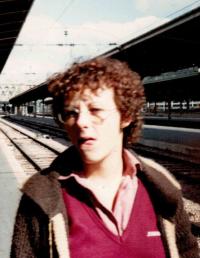

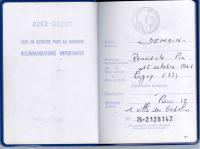

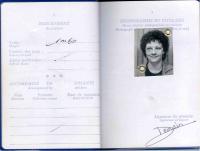

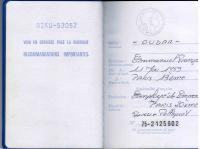

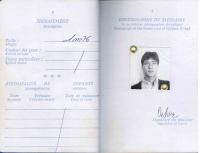

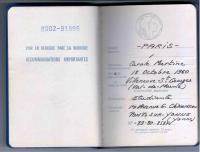

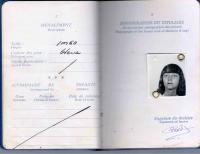

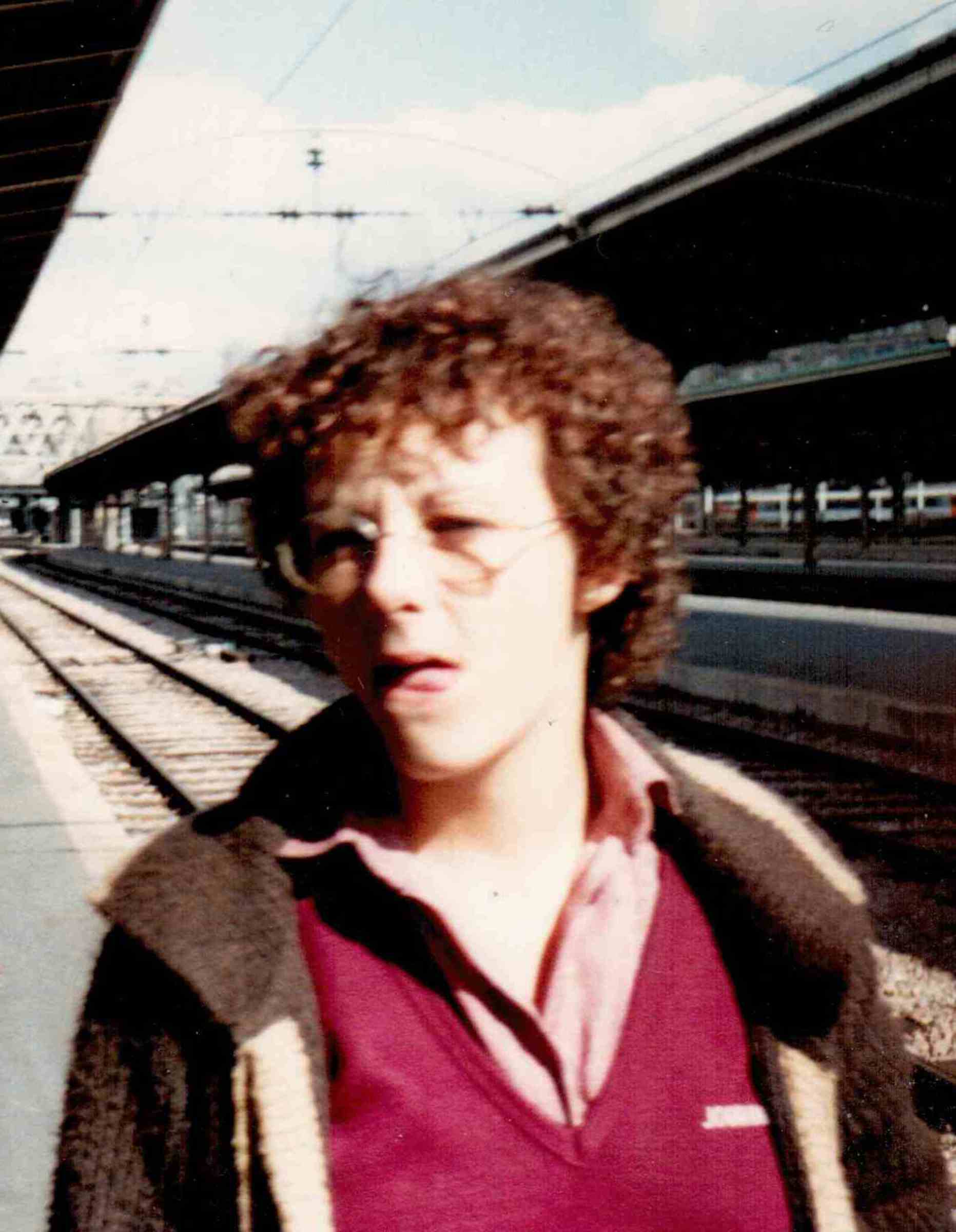

Carole Paris was born on 18 October 1960 in Villeneuve-Saint-Georges near Paris to a French couple. Her father worked as a project architect, later establishing a family business. Her mother, an accountant by training, initially stayed home with Carole and her sister and later returned to her original profession. Carole studied German and Russian studies at a university in Paris. Later, under a friends’ influence, she also began to learn Czech. In February 1981 she visited Czechoslovakia for the first time, and become very interested in the country. In Paris she got to know the Czech dissident Pavel Tigrid and his wife. She started smuggling their exile magazine ‘Svědectví’ and other literature to Czechoslovakia. During her rather frequent visits she established contacts with the underground, dissidents and Charter 77 signatories. She also became friends with Jindřich Tomeš who was, following his escape before criminal prosecution, a wanted person hiding under false identity at various friends’ places. In August 1982 Carole was awarded scholarship at a summer school of Czech language held in Brno, and she decided to smuggle Jindřich Tomeš to France. She obtained a false passport for herself as well as for him and at the second attempt in November 1982 they managed to leave Czechoslovakia for France, where Tomeš was granted political asylum. Carole finished her studies in Paris, latter marrying a Czech man and starting a family. She visited Czechoslovakia again in 1990 after the fall of the communist regime. She works as a journalist and lives near Paris.