Be strong and valiant, pray and have faith in God

Download image

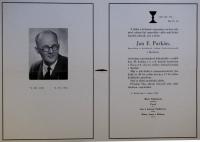

Pavel Parkán was born on June 12, 1932, in Jihlava as the only child of Jan and Marie Parkánovi. His father, Jan Parkán, came into this world on December 8, 1905, in Dvorce u Jihlavy. Since 1926, he had been a catechist in the Czechoslovak Hussite Church - CČS(H). In June 1928, he was ordained a priest and in September 1928, he was installed as a pastor of the CČS(H) in Humpolec. In January 1933, he was transferred to the tough job of serving as assistant cleric and catechist in Kolín. Here he stayed with his family at the new parsonage of the Jan Hus church. It was also here where he was arrested by the police of the German Reich on March 25, 1943, for the illegal collaboration with the local teacher Václav Kvarda, the dissemination of foreign broadcast news and anti-German preaching and public speeches. He spent his custody period together with other friends from Kolín in Kutná Hora. After his imprisonment which lasted for many months, he was sentenced to death in Litoměřice on November 9, 1944. Until his execution, he was held in several prisons. Shortly before the liberation of Leipzig, Jan Parkán and dozens of his fellow inmates were executed on April 16, 1945. The message with the pardoning of Jan Parkán failed to reach the addressee in time. The president of the republic decorated Jan Parkán in memoriam with the Czechoslovak War Cross 1939. On October 12, 1947, a memorial plaque on a church in Humpolec was unveiled and likewise, a memorial plaque commemorating him was installed in the Jan Hus church in Kolín on May 2, 1965.