None of my classmates wanted to shake my hand

Download image

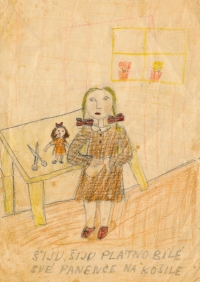

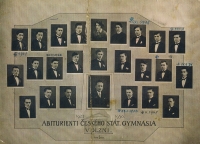

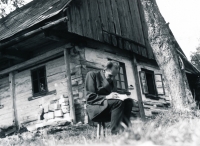

Ariana Petrová, née Matoušová, was born on May 18, 1943 in Jičín. Her parents, Zdeněk and Jarmila Matouš, were both educators who, after 1948, openly expressed their opposition to communist ideology. In 1950, Josef Matouš was fired from his job and had to work as an auxiliary worker in the Mladá Boleslav-based Škoda. Her mother was sentenced to two years for subversion of the republic, and she was serving her sentence in Ruzyně, Pankrác and Rakovník. Ariana and her two brothers were each placed in a different orphanage, and Ariana was bullied by her classmates. After her mother’s release, the family lived together again, but the trauma of dividing the family most affected the youngest Mario. In 1961, Ariana graduated from economics school and worked for a Mladá Boleslav-based insurance company. She married and had two daughters. Her mother was rehabilitated in 1968, but the family watched the political release during the Prague Spring with considerable skepticism.