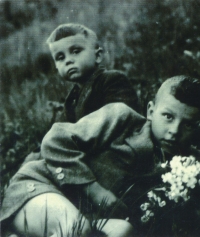

We met my father only after twenty years, when he remarried my mother

Download image

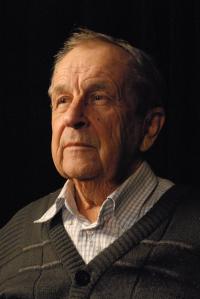

Karel Pfeiffer was born on June 14, 1936 near Margecan, Slovakia. Father Karl was a Slovak German and mother Františka Bendová was Czech. In September 1942, Karel started school in Jaklovce. In 1943, Dad enlisted in the SS troops. In October 1944, the single-parent family moved to Nové Město nad Metují to the mother’s parents. After the war, his father sought out the family, but was arrested and in 1946 deported to Germany. From 1946, Karel was in the Scout and he was significantly influenced by it. In December 1950, he repainted the portrait of Stalin as Hitler, and based on this event, the decision to admit him to the grammar school was revised. In September 1951 he had to join the TOS apprenticeship center in Dobruška. At this time, he was accused of anti-state activities due to correspondence with a former scout leader and his private dailies with alleged anti-communist content. Subsequently, at the end of October 1952, he was released from teaching. He joined MEZ Náchod as an auxiliary labourer. In February 1953, at the age of sixteen, he was sentenced by a folks court to three months in prison with a probation of two years. Before the war, he made an apprenticeship in the evening form. In 1959 he married Emilia Baling. She got a teaching position with an apartment in Suchý Důl, where they moved in 1959. They had two daughters. He did not meet his father in person until 1964. Both parents divorced their existing partners and remarried. The mother moved to Germany with her father. In Suchý Důl, Karel devoted himself to youth physical education and organized countless sports events. From 1978 he worked at Kovopol in Police nad Metují, where he was very popular for his creativity and versatile abilities. He devoted himself to photography and amateur film, which he also made a living from. He designed and manufactured badges and medals, successfully ran his business into old age and, among other things, produced cast iron attachments for hand drills.