I didn’t have the oxygen to resist any more

Download image

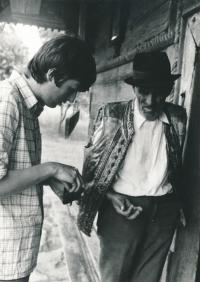

Ing. Jaromír Plíšek was born on 20 May 1955. He grew up on the outskirts of Prague, in Bílá hora. His father was a technical engineer, his mother suffered from a heart disease and remained at home as a housewife. His childhood was influenced by his school years at the local primary school and his brief period as a member of the local Scouts troop. He attended the Secondary Technical School in Dušní Street and went on to graduate from transport engineering at the Czech Technical University (CTU). Around that time he converted to Christianity and joined the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren (ECCB). He played in Christian folk bands and helped prepare the extensive songbook Svítá (Daybreak). In early 1977 he attended the funeral of Jan Patočka, respected philosopher and first spokesman of Charter 77, which caused him trouble at school. During his one-year compulsory military service, which he began in the Military Arts Corps, he experienced the tense situation caused by the looming threat of an invasion into Poland on the turn of 1980-1981; the following spring he considered boycotting the elections, but in the end he gave into pressure and circumstances and attended the “elections” just like the vast majority of Czechoslovak citizens at the time. Already during his student years he travelled to Romania, where he made contact with the small Czech community in the Banat region. He continued to sympathise with expressions of opposition, and he himself participated in such activities. At a manifestation on 28 October 1989 Jaromír Plíšek was briefly arrested by the police, but this was soon forgotten in the rush of the Velvet Revolution and the collapse of the Communist regime a few weeks later. The witness became a lay member of the Synodical Council of the ECCB, in 1993 he found employment as a diplomat at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic, his postings included those of ambassador in Hungary and Romania. In 2013 he was to be appointed ambassador in Slovakia, but the newly elected Czech President Miloš Zeman decided instead to give the post to the previous president’s wife Livia Klausová.