You could live freely even under the communists, as long as you didn’t ask what was allowed too much

Download image

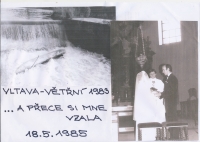

Jan Rabiňák was born in Prague on 5 January 1960. His father worked as a waiter on the international dining cars of Czech Railways and refused to collaborate with the intelligence service in the early 1960s. From 1968 to 1970, Jan Rabiňák was a member of a scout troop before scouting was banned again. Since 1972, as a boy and later as a leader, he participated in secret ‘Salesian cottages’ - holiday stays for children with a focus on Christian education. He graduated in 1978 and started studying water engineering at the Czech Technical University. After graduation he worked at the Water Research Institute. He married Ivana Tomanová in 1985 and raised four children. Since the 1970s he studied theology in residential seminaries. After the Velvet Revolution he completed his studies officially at the Theological Faculty. He has been a scout leader since 1994 when he founded a cubs team in Břevnov. He was actively involved in Scouting until 2020.