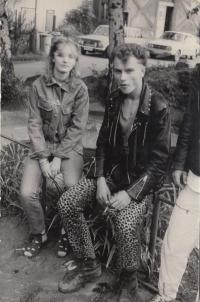

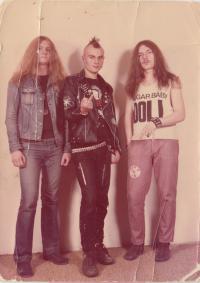

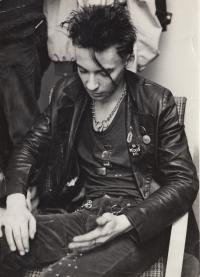

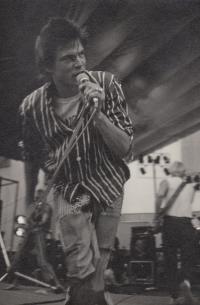

Punk was a revolt against all that is above us

Download image

Jan Rampich was born on May 30, 1966, in Pilsen. His father was Czech-Slovenian, a projectionist and labourer at the Railway Maintenance and Engineering Works (ŽOS), his mother was the telephone operator at Communications Company. His brother Erik is nine years younger. The witness finished his primary school in 1981, then went on to study the Secondary Technical School in Pilsen. From the age of fifteen, he dedicated more attention to hard music than school and subscribed to the punk lifestyle. At that time his parents divorced. He used to flee home, attended concerts, went to Prague to hang around with his friends from the punk scene. His look was provocative, was often summoned for interrogations by the Secret Police. He failed to complete his school and went on to work in the Railway Maintenance and Engineering Works in Pilsen. Since the mid-1980s his originally purely music punk interest merged with political protest, although he did not want to do politics. He used to sign various petitions, in 1986 he signed Charter 77, in summer 1989 Several Sentences. He distributed Infochy, the samizdat journal Vokno, established and edited from his bedsit the journal Pevná hráz. He was criminally prosecuted for his activities but before the trial could take place the November revolution came. After 1989 he worked in various jobs, spent a year and a half in the Netherlands around 2012, where he worked as a welder. He has not children and has been married five times.