There were 120 of us in our troop and only four of us survived

Download image

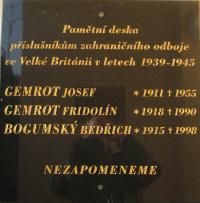

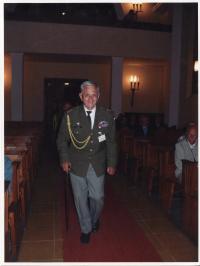

Otakar Riegel was born in 1925 in Rychvald. Before Christmas 1943 he was forced to join the wehrmacht. After five-months of training near Hannover he was transferred to Normandy. During the Allied invasion he was buried in a small shelter for several hours amidst the bombardment. Only four soldiers out of the 120 men in his troop survived. After a time in captivity he applied to join the Czechoslovak Independent Brigade and was assigned to the 2nd battalion of the 3rd column. After a short training session in Great Britain, he took part in the siege of Dunkerque as a tank driver. After the war he worked as an office worker in the Czechoslovak ironworks. After the Communist purges he was dismissed in 1948 due to having served in the western army. Later he worked as a miner in the mine Michal and became a section head after completing distance learning courses at an industrial school. He was not allowed to study further. For several years he was employed by the mining bureau. He was the chairman of the Union of Antifascist Fighters in Slezská Ostrava. Otakar Riegel passed away on September, the 6th, 2013.