We’ll send you up a chimney

Download image

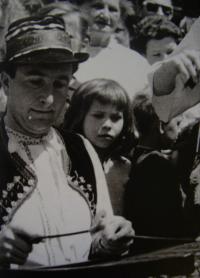

Dr. Ing. Jiří Schreiber, CSc., was born on 22 August 1925 into a Jewish family in Lipník nad Bečvou. He completed primary school and then attended the Association Jewish Grammar School in Brno. When the school was closed in May 1940, Jiří began working in Lipník as a volunteer at a car repair shop. On 26 June 1942 he and his family were deported by an AAs transport to the Terezín ghetto under number 766. He was quartered in the Sudeten Barracks and worked first in the Jewish administration, later as a body carrier, and finally at a car repair shop. He and his father departed for Auschwitz concentration camp on 28 September 1944, but thanks to his experience from the repair shop, in November 1944 he and his father managed to get sent from Auschwitz to Meuselwitz labour camp near Leipzig, to an auxiliary facility not far from the central concentration camp of Buchenwald. He worked at the HASAG factory, which produced ammunition for the Wehrmacht. In mid-April 1945 he was sent on a death march, but he and his father managed to escape from march and reach the villages of Manětín and Valdměřice, north of Pilsen. On 1 May 1945 the two of them travelled to Prague, where they took part in the Prague Uprising. On 12 May 1945 Jiří Schreiber set off to Terezín to look for the rest of his family. His mother, brother, and grandmother were all murdered in Auschwitz. After returning to Lipník Jiří completed his grammar-school studies and applied to university. He graduated from chemistry at the Brno University of Technology. After obtaining a doctorate degree he found employment as an assistant professor at the University of Chemistry and Technology in Pardubice. In 1968 he was stripped of his functions; he went to work as an interpreter and adviser for chemists. After 1989 he renewed his university tenure. Jiří Schreiber lived in Pardubice. He died there on 4 December 2012.