Compared to what others had to endure, it was a walk through the Garden of Eden

Download image

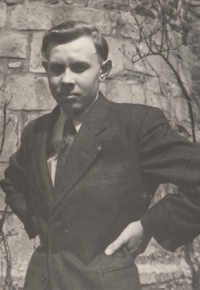

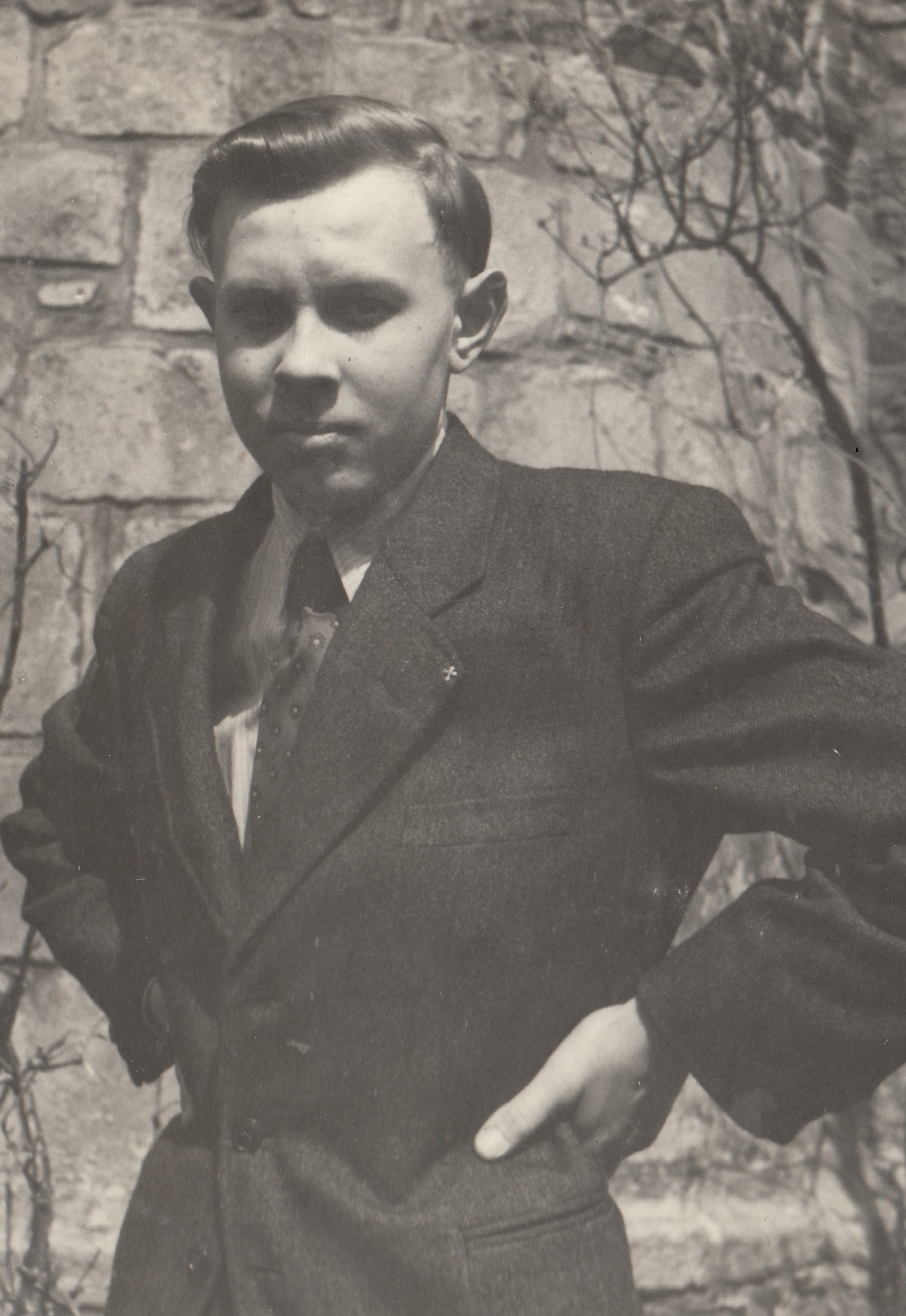

Josef Sedlák was born on 3 July 1937 in Jihlava. He grew up in a Catholic family and his faith accompanied him throughout his life. In Jihlava he experienced the liberation and the expulsion of Germans, some of whom were people from the neighbourhood. Until 1948 he was a member of Orel. He wanted to become an car mechanic but had no choice, so he apprenticed as a shop assistant. He experienced the currency reform of 1953 in his job. From a young age, he was associated with a group of religious friends with whom he made trips, held meetings, and also copied religious literature. From 1957 onwards, the group faced interrogations and eventually a trial. As a juvenile, Josef Sedlák ended up serving an eight-month sentence for “subversion of the republic”, which he served in Jihlava. After his release, he began working in the construction industry. In November 1989, he was working on a construction site in Prague and was able to participate in various rallies and demonstrations. He and his wife, whom he married in 1963, raised five children, and in 2018 they had 20 grandchildren. In 2024, he was living in Jihlava.