“I lost my faith during the war, for I could not understand how God could allow something like this

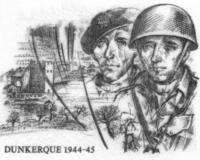

Edgar Semmel was born in 1924 in Teplice-Šanov from a family of a Jewish textile traders. In 1939, the family emigrated to Palestine. In 1943, he voluntarily joined the Czechoslovak army. After his training, he was deployed to Dunkirk. In 1947-1952, he studied at the Leningrad Polytechnic Institute. He worked at the ČKD Praha company and lectured at the University of Economics in Prague. He was actively involved in the events of 1968 and displayed his objection to the normalization period by retiring (as a war veteran he was permitted to retire earlier). Near the end of his life, he was active as a high official in various organizations for senior citizens.