The worse thing during normalisation was how quickly people changed

Download image

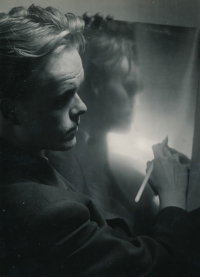

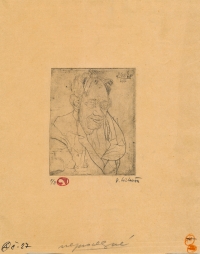

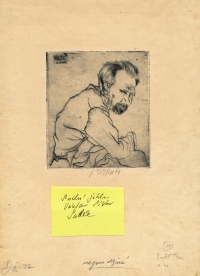

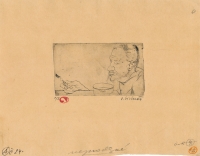

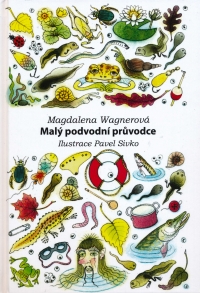

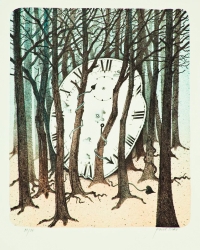

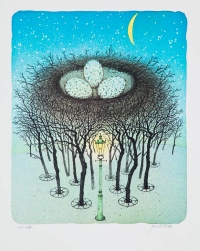

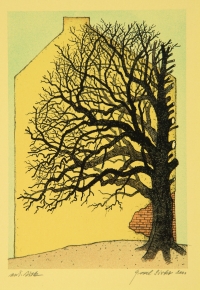

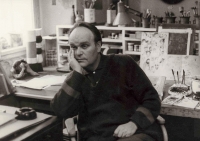

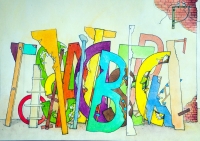

Pavel Sivko was born on 24 January 1948 in Prague. His father Václav Sivko was a painter, graphic artist and illustrator, his mother Libuše was a housewife. Pavel has a sister two years younger. In his youth, besides his father, he was also influenced by his father’s friend, photographer Josef Sudek. In 1967 he graduated from the art school on Hollarovo Square and the same year he was admitted to the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design, where he studied in the studio of Jiří Trnka. After his death in 1969, the studio was taken over by Zdeněk Sklenář. He graduated from the school in 1974. After signing The Two Thousand Words and resigning from the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Pavel’s father was unable to work professionally, was prevented from illustrating books, and could not exhibit or publish, which he took very hard. He died prematurely in 1974. Due to his participation in the anti-occupation strikes after the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops, Pavel was unable to serve the compulsory military service in the army art group for background reasons, but had to enlist in a labour battalion in Cheb. After the service he found employment as a book illustrator and graphic artist, working freelance and avoiding political subjects. In 1977, when his wife Jitka was expecting a child, he succumbed to pressure from his surroundings and, fearing that he would lose his job, signed the so-called Anticharter. He spent November 1989 at the demonstrations and helped in the press centre at Mánes with the production of leaflets and posters. After the revolution, he worked for six years in the art department of the Mladá fronta publishing house, and from 1997 to 2020 he was a professor at the Václav Hollar Secondary School of Art in Prague. He was married to the artist Jitka Walterová Sivková.