“We were making music and we didn’t care about what was around us.”

Download image

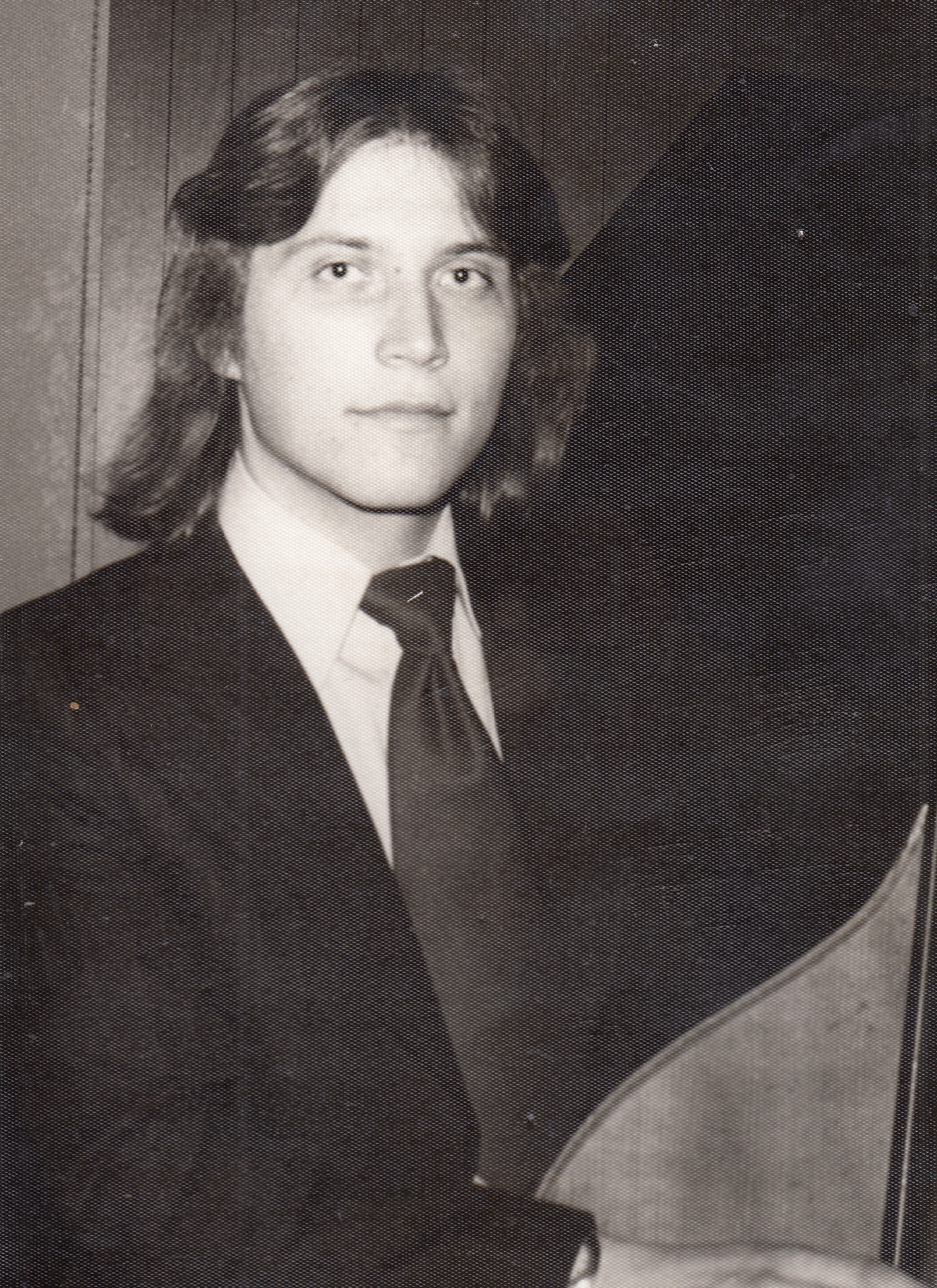

Musician and sound engineer Štefan Škulavík was born on 12 September 1958 in Karlovy Vary. His father Štefan Škulavík Sr. came to Karlovy Vary from Slovakia with Svoboda’s army at the end of the Second World War. His mother Anna, née Scheertl, was of German origin. She came to the region with her parents in the autumn of 1938 as part of the German repopulation of the areas that were being abandoned by the Czech population after the occupation of the Sudetenland. Štefan grew up in the village of Všeborovice, which later became part of Karlovy Vary. The family lived a simple life and did not care much about politics, but his parents were members of a choir and Štefan’s brother Josef performed with the jazz-rock band J4. Štefan soon found his way to music and started studying at the Secondary Industrial School of Musical Instruments in Kraslice. During his high school studies he founded his first big beat band Zkrat. It ceased activity in 1980, when he was called up for basic military service. After returning from the army in 1982, he founded the band Benefice, which performed mainly at parties in the Karlovy Vary region. After a police intervention at a Benefice concert in 1983, the band was threatened with a ban, so the musicians decided to change their name to Barock. The new founder was the House of Culture in Ostrov nad Ohří. Barock was also mainly a regional entertainment band. In 1988, however, the band was invited to take part in the Sokolov Festival of Political Song. The musicians were aware that it was a strongly pro-regime event, but rather than as a sign of loyalty to the regime, they saw it as an opportunity to raise their profile and move to a higher level. One of their songs made it onto the long-playing album Planeta míru, which was released on the occasion of the festival. In the end, they were not allowed to perform at the gala in Sokolov because the lyrics were deemed insufficiently political. Barock continued to perform at parties, but faced further political problems after a police crackdown at a concert in Lomnice u Sokolov. Shortly afterwards, Štefan Škulavík left the band under the influence of a strong experience from a concert of the band Europe in Munich. He suddenly found the level of their band insufficient in this comparison and decided to quit music. In the November days of 1989 he helped with the sound system of the demonstrations in Karlovy Vary. In the 1990s he went abroad for work and worked on organ repairs in the Karlovy Vary region. Around the year 2000 he set up a sound studio in the Ostrov House of Culture, where he also ran the theatre Točna and a music club. However, after disputes with the management of the House of Culture, he left this place. He continues to work as a sound engineer in the Karlovy Vary region.